Climate Change is Dead

The end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world

One of the strange mercies of the last week of the year is how the machinery pauses just long enough to hear your own breathing again. And yet, when you get all that breathing room, the thoughts you’ve been pushing away suddenly show up, like they’ve been waiting patiently for this exact moment when they have nowhere left to hide.

So naturally, I’ve been thinking about the year that’s ending and the one ahead.

I’ve spent most of my adult life inside a conversation I never trained for, but never really left either. It’s certainly not the only thing I’ve done since finishing high school, but it has been the invisible thread running through my life. In boardrooms and kitchens, in Patagonia and elsewhere, in essays and private conversations, I’ve been someone who talks about climate change, and that has shaped the kind of adult I kept trying to become.

And then, toward the end of this year, I realized I had to stop.

The planet, unfortunately, didn’t stop warming. The crisis, unfortunately, didn’t go away. No. What happened was that the words suddenly started feeling like they were not pointing in the right direction.

It felt like holding a map that once made sense, only to realize the roads had all changed. Follow the map carefully and you still get lost. Not because the map is lying, but because it no longer matches the terrain.

Say “climate change” and watch what happens.

The air fills with pitches, dead-end confrontations, and oxymorons. Carbon capture. Geoengineering. Sustainable growth. Dashboards and targets and heroic diagrams. The problem gets framed as something to be solved, preferably at scale, preferably for profit, preferably without asking who pays or what gets consumed along the way. As if we were standing beside a dying body arguing about which pill to prescribe, never asking why the body is breaking down.

This is not just another problem to solve with better gadgets.

Because, for starters, what we’re facing isn’t a problem, as in something you can fix. This is a predicament: something you have to navigate, adapt to, or endure.

Problems have solutions. Predicaments have consequences. And problem invites engineering while a predicament demands reckoning.

So the moment we start from “climate change,” we step onto a board designed by people who believe every alarm is a business opportunity. The conversation slides, predictably, toward fixes that deepen the underlying trouble. More extraction to build the tools. More energy to deploy them. More complexity and more B Corps and 1% For the Planet labels layered onto a system already straining under its own weight.

All of the above promise continuity and interventions designed to preserve the shape of the world we know. But the real issue sits upstream from emissions charts and temperature targets. It’s the simple, brutal fact that we are consuming faster than the living world can regenerate.

Energy. Soil. Water. Attention. Time.

That reality doesn’t fit on a slide. It doesn’t sell well. It doesn’t end with a ribbon-cutting ceremony. Yet here we are, arguing about speed while pretending there isn’t a wall ahead.

The schemes are already on the table. Desperate geoengineering proposals. Borders hardening. Walls rising. Exit visas quietly discussed while those already displaced are framed as threats instead of symptoms.

All of it driven by the same instinct: defend the world as we know it, whatever the cost.

But the end of the world as we know it is not the end of the world.

Unless we learn to inhabit that distinction, we will burn the future trying to preserve the present.

The Underlying Infection

We’re facing something so complex and overwhelming that the two-word label we use to describe it, “climate change,” has become too small and too familiar. It’s like calling a car crash “transportation disruption”: technically accurate, but missing the reality of what’s happening.

The damage is visible, tangible, and unfolding around us right now.

It’s floods that don’t announce themselves and show up like a door kicked in. It’s fires that turn a whole summer into one long cough. It’s heatwaves that make shade feel like a thin lie. It’s weather patterns that get stuck, like the planet has a hand trembling on a gearshift it can’t find.

In Patagonia, I’ve watched lakes run warm in places my body still insists should hurt to touch. Glaciers that stood like stone in the mind now calve icebergs the size of cities into a warmer sea. And far from here, in places where the calendar used to mean something to farmers and families, monsoons arrive weeks late or not at all.

How much louder do these events need to become before we stop pretending our current approach is working?

As these signals move into uncharted territory, affecting every single person in the world, directly or indirectly, in undeniable ways. the trail inevitably leads to a fork in the road.

On one side, there’s the massive mainstream highway with tons of lanes all flowing in the same direction. On this flashy highway, you’ll find tech billionaires, investment banks, government agencies, and even some progressive groups, all riding shoulder to shoulder despite their differences. What unites them? A shared belief that we can fix our problems without fundamentally changing how we live. The pitch is: “Don’t worry, we can keep consuming, keep growing the economy, keep living basically the same way. Because the machine isn’t broken; it just needs better software (and you can even power it with a solar panel!).”

This approach is appealing because it doesn’t ask anyone to give anything up. You can keep your lifestyle, your conveniences, your expectations. We’ll just optimize and innovate our way out of the crisis: build more, scale faster, engineer solutions.

Then there’s the small path. The unsexy one. A trailhead most people walk past because it doesn’t look like a solution. It branches into many paths, because it’s not a single program; it’s people building resilience close to the ground, learning how to live with less and becoming competent again in ways that don’t fit on a dashboard. It’s learning how to grow food, fix things, and help each other when systems fail.

This path accepts that we can’t maintain (delusional) endless growth and technological progress forever. But it doesn’t see that as doom, but as an invitation to build something more human-scale, where communities are resilient because people are actually capable and connected, not scrolling under the AC.

Nobody is giving up here. Instead, they are getting ready for a world that works differently than the one we were promised. And many people are already quietly living this way, right now.

Most people don’t want to choose between these paths because choosing means admitting what we’re standing inside. But here’s the part that won’t let me go.

The fate of industrial civilization wasn’t “sealed” by bad politicians or oil companies alone. It was baked into the operating system the moment it began, because every complex human society, the Greeks, the Persians, and ours included, survived by pulling more out of a landscape than that landscape can put back in time.

That self-destructive setup has a name: ecological overshoot. And that’s the concept I was hunting for this end of year, when the climate-change words started slipping from my hands.

I know I’ve used it before, but from here on out, I’m treating overshoot as the root, not climate change. Overshoot is upstream. It sits behind warming and deforestation and pollution and soil loss and water scarcity and depletion and acidifying oceans and extinction and societal and political fracture.

Climate change is the fever. Overshoot is the infection.

Treat the fever and it comes back. Ignore the infection and it worsens.

And we’ve already run past limits that used to feel like abstractions. We’ve crossed seven planetary boundaries and one tipping point, the kind of invisible line-crossing where the world keeps moving but the rules underneath it start to change.

And it all starts with energy, the invisible currency that makes literally everything possible. Pull the energy plug on any system, and that system stops. No exceptions.

Humans run on energy in two channels. Your body runs on food. That’s endosomatic energy, the calories that keep your heart beating and your brain working. But humans also use energy outside our bodies, or exosomatic energy. Every time you turn on a light, drive a car, heat your home, or use a machine, you’re tapping into this external energy source.

So what we call “the economy,” “technology,” or “progress” aren’t really separate things; they’re just different ways we’ve figured out how to capture and use more of this external energy.

And unlike our appetite for food (which has limits), our desire for external energy has no ceiling. We always want more convenience, more speed, more comfort, more power.

Well, population doesn’t follow desire. Population follows food.

No energy → no food → no people → no civilization.

It’s that simple and that fundamental.

So when we talk about energy, we’re really talking about the foundation that makes everything else possible, including how many people can exist on the planet.

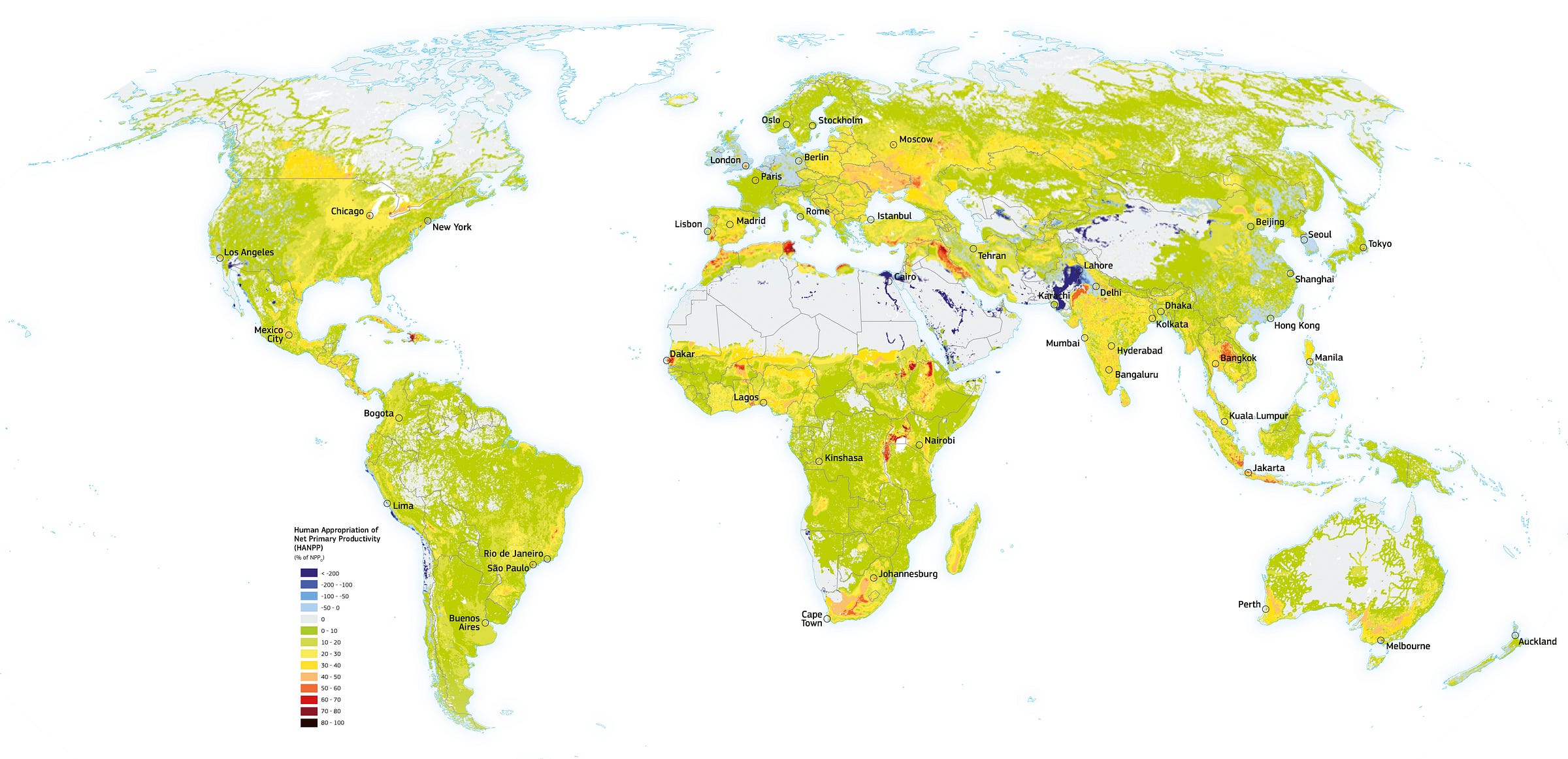

All life on Earth runs on solar energy that plants capture and turn into food. This total amount of biological energy available is called Net Primary Productivity (NPP), the planet’s energy budget that all living things have to share.

Organisms don’t cooperate to share this energy fairly. They compete for it. And any strategy that grabs energy faster than competitors tends to win in the short run, even if it leads to collapse later. This is the Maximum Power Principle (MPP): systems naturally evolve to maximize their energy intake and use.

You can see this truth on a trail.

When you’re starving, you don’t carefully ration the berries on the bush—you strip it clean. When you’re freezing, you don’t worry about next winter’s firewood—you burn what you need now. You don’t do this because you’re immoral. You do it because your immediate needs always come first over abstract future concerns.

When you’re hungry, you strip the bush.

When you’re cold, you burn the wood.

“Later” is a luxury made possible by technology that created surplus.

Technology is how we capture that surplus. And once a technology allows population growth, abandoning it means famine. Lose the tool, lose the surplus, lose the people. So we defend it. We call it progress. And we become trapped by it.

Fire did this.

Agriculture did it again, at a much larger scale

Farming multiplied calories, created storable surplus, shortened birth intervals, and exploded populations. It also turned ecosystems into fuel depots, a process measured as Human Appropriation of Net Primary Productivity. Early societies tripled or quadrupled per-capita energy demand before fossil fuels even entered the picture.

Ever since survival depended on heat, humans have burned something daily. More people means more burning. Agriculture amplified that by increasing population, clearing carbon-storing land, reducing sequestration, and adding methane through domesticated animals.

So it doesn’t matter how high the “ceiling” is, how many people agriculture can theoretically support, because the method itself—continuously consuming the foundation that makes it possible—is destructive.

Scale that logic to a planet and the outcome isn’t mysterious. You burn through what exists, and then it’s gone.

We keep going because stopping means collapse. We keep going because continuing also means collapse.

The difference is just timing.

A Rocket To Mars

So there’s a rocket leaving planet Earth (probably filled with very wealthy people) with intentions of inhabiting Mars because our planet has given up.

To keep going, it constantly needs fuel, just like every other rocket. Yet this one is not like every other rocket, because as it travels through space, it also destroys what it leaves behind, meaning there’s no return.

Even more, energy still obeys the laws of thermodynamics. The Second Law is especially rude about Martian dreams. Once something is spent, it’s gone in the form you needed. You can rearrange and transform, but you can’t conjure a permanent surplus out of a finite world.

Flows slow eventually. And the rocket might not even make it all the way.

That rocket is our civilization.

We think we can just keep going forward by pulling resources (oil, minerals, forests, fertile soil) and convert them into cities, factories, food systems, and waste. This process creates the infrastructure that keeps billions of people alive. But it also damages the ecosystems, depletes the resources, and destabilizes the climate that all of this depends on.

So we’re simultaneously:

building the machine that sustains us

while dismantling the ground it stands on

All life feeds on death. Everything we put in our mouths, everything that allows us to live, is the gift of another life.’ However, our modern way of life runs on millions of years worth of death from ancient plants and animals that died millions of years ago, all concentrated and burned in a single human lifetime.

How could anything we do be worth that?

Collapse, as counterintuitive as it may sound, is baked into the operating model.

Because, just like rockets, the system survives on flux, continuous flows of energy and materials.

When flows increase, the machine grows. When flows stall, it strains up everywhere: wages, politics, trust. When flows tighten, it breaks. And when flows stop abruptly, the crash can be fast enough to feel like an ambush.

Even before total energy declines, collapse dynamics can start.

If energy gets harder and more expensive to extract, or if population grows faster than aggregate energy, energy per person falls. Living standards drop. Food, heat, shelter, basics get pricier. Economies strain. Politics lurch toward extremism. People start fighting over the shrinking margin, long before the machine runs out of fuel.

Any similarity with reality is no coincidence.

Can we downsize this predatory Jenga while people are still living in it? Unfortunately, not. Because we have two problems:

The competition problem: Humanity is in an invisible race where slowing down means someone else wins and takes your resources. That’s the maximum power imperative. Any group that voluntarily uses less gets overtaken by groups that don’t hold back. You don’t want to be the only car that slows down on a busy highway—otherwise, you just get passed.

The dependency problem: Our modern systems are like a house of cards where every card matters. We need specialized parts, global supply chains, and constant energy just to keep things running. You can’t just pull out a few cards and expect the structure to hold. Trying to “live simply” sounds nice, but when you have billions of people depending on complex food systems, electricity grids, and supply networks, removing pieces causes the whole thing to fail faster than you can adapt.

This is the repeating shape of overshoot-collapse.

Resource grab, growth, overshoot, breakdown.

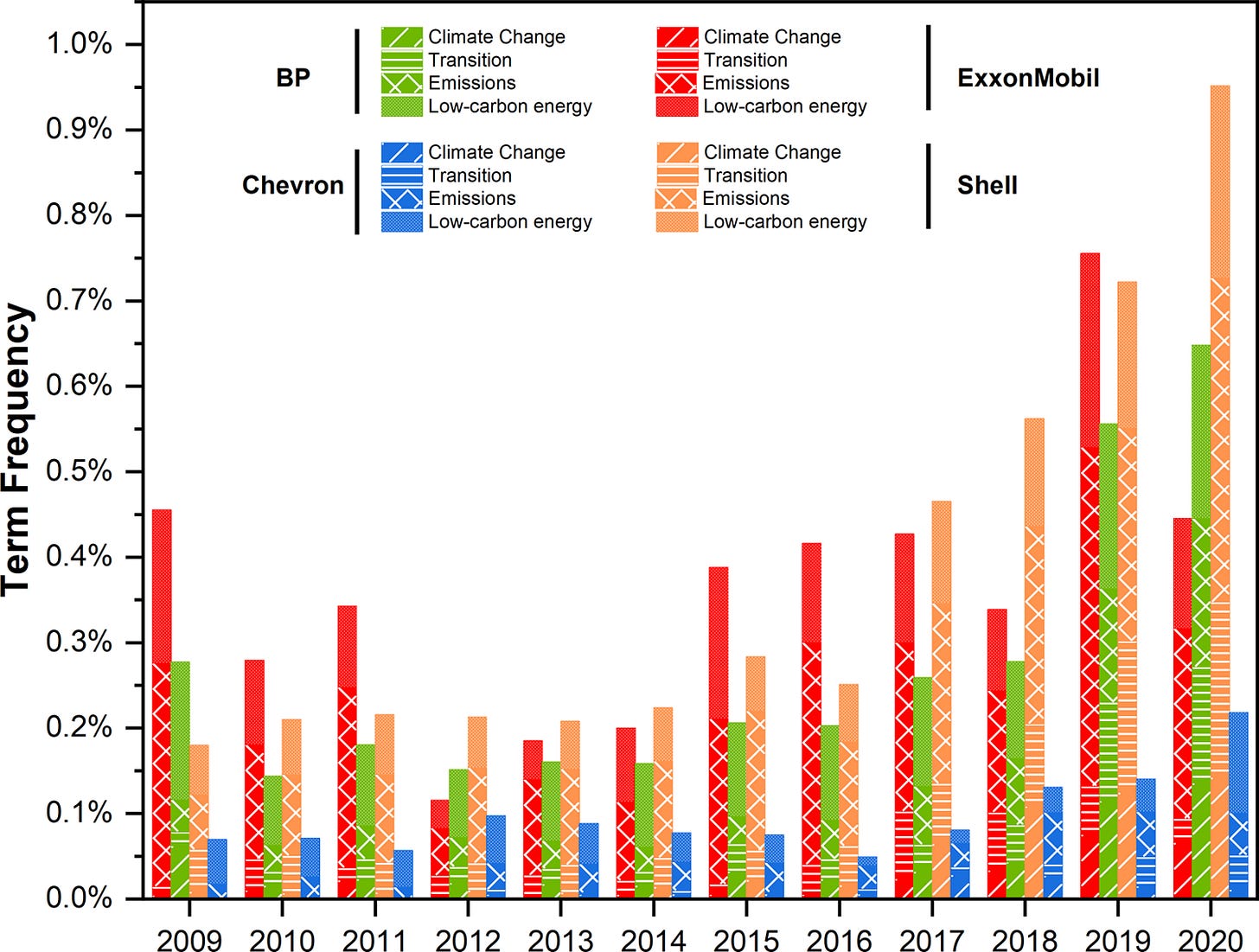

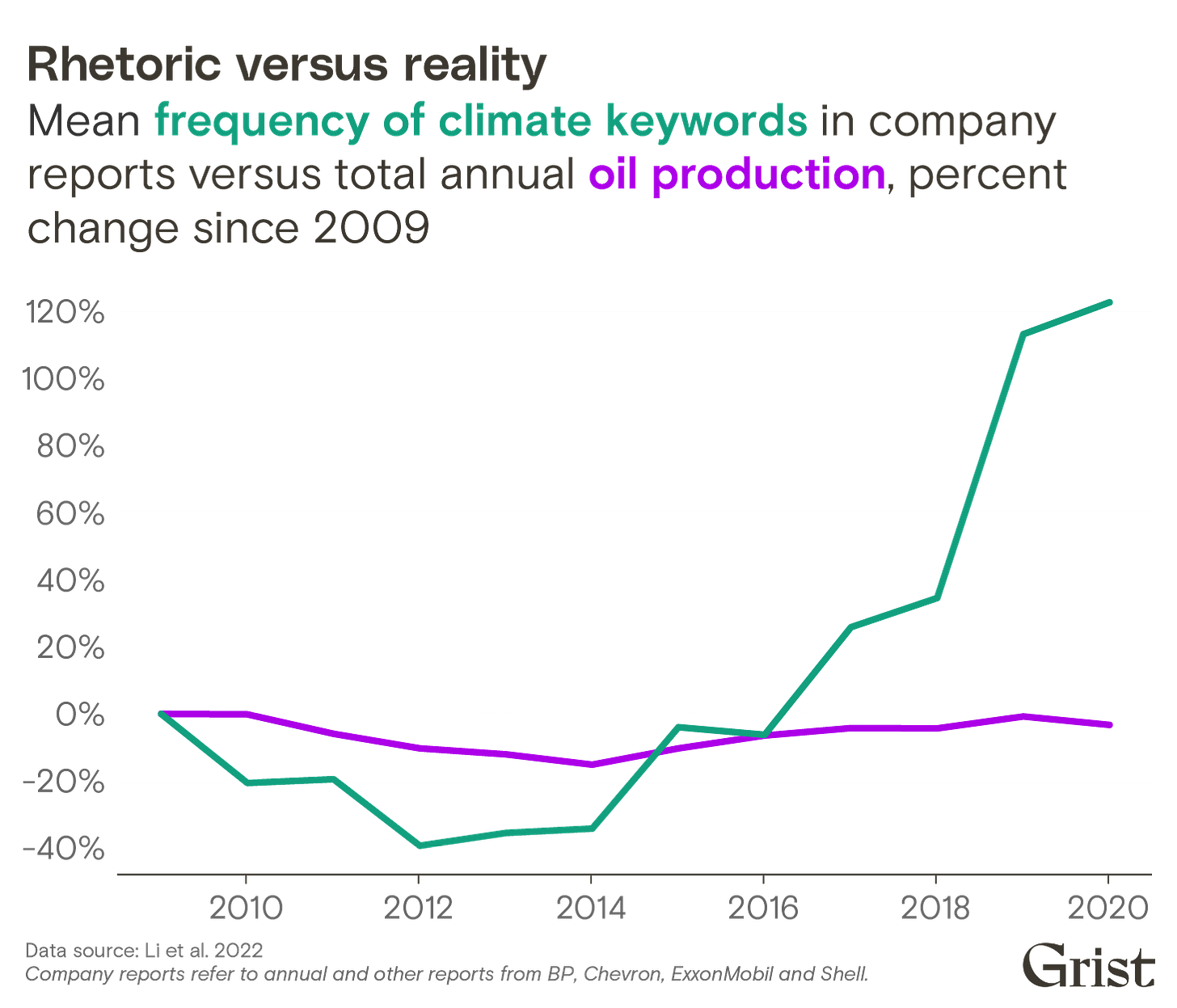

And this is why I think the language of climate change is about to become more captured than it already is.

It will be owned by the big path, the engineers and marketeers promising continuity through fixes that keep the machine running. Any conversation that begins inside the politicized frame of “the science” slides toward solutions, because the frame itself points there. But remember: this is a predicament, so there’s no solution.

The people drawn to the small path are already in a strange position. Climate change is spoken in the voice of management, optimization, control.

That’s why we need another place to start, another language, if we want to talk about the depth of the trouble without being recruited into building the very future that deepens it.

An Email You Will Never Receive

Subject: We Made A Mistake — The Climate Will Be Fine

Date: January 1, 2026

From: The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

To: Everyone

Dear humanity,

This is an unusual message to send at the start of a new year. It is also an inescapable one.

We owe you an apology.

After an extensive internal review, cross-checking decades of models, observations, and assumptions, we must inform you that we made a fundamental error.

The correction is this:

You can burn all the fossil fuels you want.

Coal, oil, gas. Every last reserve. The atmosphere will absorb it. The climate system will remain stable. No runaway warming. No destabilization. No planetary feedbacks to worry about. The equations resolve: the planet’s temperature remains within familiar bounds.

In short: the climate will be fine.

You may proceed.

This announcement could normally be followed by relief and sound like permission. A collective sigh might move through the global economy.

Yet, with climate change suddenly off the table, does everything else become acceptable?

Look around.

The rivers that no longer carry fish. The open pits carved into mountains. The soil stripped, compacted, poisoned. The coastlines armored, dredged, privatized. The forests cleared, burned, replaced with pasture or tailings ponds.

The map no longer fits the land.

If none of this affected the climate, would it suddenly be acceptable? If the oil sands and wells and rigs were not warming the atmosphere, would they look wise? If mining, even if it is for lithium for electric cars left aquifers empty but stabilized temperatures, would it feel justified? If forests fell, species vanished, and landscapes became sacrifice zones without touching global averages, would that make this a good idea?

Our suspicion, based on years of watching societies react not just to data but to damage, is NO.

Even without atmospheric consequences, this would still look like a reckless way to inhabit a finite world.

And that is the point we have failed to communicate clearly enough: Climate change is dead. But because the words no longer tell us the truth we need to hear.

The deeper predicament remains untouched: a civilization organized around continuous extraction, growing throughput, and the assumption that the living world exists primarily as fuel, feedstock, and waste sink. A way of life that must keep expanding simply to remain standing.

Climate change turned out not to be the disease, but one of its most visible symptoms.

This email does not tell you what to do next. That was never our mandate.

It does ask a question we cannot answer for you:

Is this actually a wise way to live on a planet, regardless of atmospheric consequences?

If the answer is no, then the work ahead was never only about emissions, targets, or temperature curves. It was about how you relate to land, energy, limits, and each other. It was about whether a society can learn to live within what can be regenerated, rather than burning through what cannot.

Sincerely,

All the respectable scientists in the world.

Bravo! This post covers a huge amount of ground in a relatively concise and accessible way.

"Climate change is the fever. Overshoot is the infection.

Treat the fever and it comes back. Ignore the infection and it worsens."

Exactly. My own work is to take this one step further. If Ecological Overshoot is the disease, then at the root of *that*, our flawed value system is like a compromised immune system.

We have two ways of measuring success: qualitatively - where success means we have enough; and quantitatively, where More is ALWAYS Better. Both have a role to play, but when the second completely trumps the first (as it does now) we get ecological overshoot. Number-based values have NO concept of sufficiency. And here's the kicker: The impossibly infinite pursuit of 'more' is at the root of every aspect of ecological overshoot.

You spoke of endosomatic energy (what a body needs to live), and exosomatic energy (what we use outside the body). The first form of energy has a qualitative measure - there is a clear range that defines sufficiency. More is not always better. Too much food, or water, or internal heat, is *not* better. Exosomatic energy is more problematic. Some of it is qualitative - what we need to survive - but the vast majority of our external energy usage is utterly wasted. Being faster, owning more, being wasteful. Extreme examples include AI data centres so that people can post pictures of themselves in outlandish settings, or have conversations with large-language-models instead of other humans, or can have a three-page essay summarized because they can't be bothered to read it for themselves.

Our exosomatic energy and resource consumption is where we have decided that More is ALWAYS Better. Some of the wrong turns were subtle. Cooperation and collaboration are prerequisites for progress, and in our economic models, one form of community group effort became the corporation. However, instead of creating such entities to accomplish a fixed task - instead of baking sufficiency into their definition - we programmed them to be entirely number-based, to always seek MORE as their ultimate goal.

Think about it - when we say their purpose is to "maximize profit", profit is a number. There *IS NO MAXIMUM*. I call this our Value Crisis.

If you don't like the fever symptom that is climate change, and you wisely decide to address the underlying disease which is ecological overshoot, you have to do so by improving our immunity to the values that lie at the heart of it all.

You know, Ricky, there's a huge difference in the emissions between income groups, and I wish that would be addressed more.

I live frugally, am vegan, don't drive and have paid attention to energy use for a long time, and will continue to. But I wish the emissions of this group would be emphasized more. It's not about the number of people, many of whom don't have much of an impact on the environment, it's the filthy rich who travel around in their private jets, own many mansions and yachts and seem oblivious to the emissions they create.