Earth Is Barreling Toward a Second Year Above the 1.5°C Threshold

Last year was the warning — this year is the reckoning: welcome to the Age of Overshoot.

If you could ask a sea turtle why small increases in global temperature matter, you’d get a mouthful — of sea grass, maybe, but also something heavier: a lifetime of adaptation pushed to the edge. They’ve survived since the age of dinosaurs, gliding (but also enduring) through life like time didn’t exist. Volcanic eruptions, meteor strikes, shifting continents.

But now? A few tenths of a degree might do them in. The temperature of the sand where female turtles bury their eggs influences the gender of their hatchlings. A world that leans just slightly warmer skews the outcome. More heat, more females. At 31.1°C (88°F), it’s all girls. At 27.8°C (82°F), it’s all boys. And anything in between? A shrinking chance for balance.

The result is a prehistoric animal gambling her lineage on grains of sand that are now, literally, too hot to carry her future. Because, in some rookeries, more than 99% of hatchlings are female.

The biological coin toss now hinges on decimal points.

So you might be wondering, “Why should I care if temperatures go up another tenth of a degree or even a full degree? What’s the big deal? Isn’t that what happens between morning and night anyway?”

The answer is: a lot.

Because our planet runs on tight margins, and temperature is a boundary line drawn by physics and enforced by biology. A few tenths of a degree can mean the difference between life and death — not just for sea turtles, but for every system alive.

Take our own bodies. Human life is calibrated to a narrow thermal window. The average healthy adult temperature is 37°C (98.6°F). Push that up by just one or two degrees, and we spiral into fever — delirium, failure, death. Our productivity and cognitive function drop sharply outside the Goldilocks zone of 22°C. That’s why we chase air conditioning. That’s why we sweat. Our bodies know better than our politics.

When ice crosses 0°C, it melts. When ocean water warms, it expands. When atmospheric heat crosses a wet-bulb threshold, the human body can no longer cool itself — even in the shade, even if you’re drenched in sweat. Beyond 35°C wet-bulb, it’s not just uncomfortable. It’s potentially fatal.

Nature isn’t built for improvisation. Plants and animals can’t flee to cooler offices or sip iced coffee in front of a fan. They’re shackled to place and survive within specific, defined habitats. Push them outside those zones — and they break. They die. They go extinct.

So let’s talk about that number we keep hearing — 1.5°C. The so-called “safe” threshold. The target that’s been turned into a climate catchphrase, trotted out by politicians as PR chants and splashed across endless reports. But what does it actually mean?

To many, it may sound laughably small. What is a 1.5°C difference in your morning coffee, right? But on a planetary scale, 1.5°C is the line between ecosystems adapting and collapsing. Between food security and crop failure. Between habitability and exile.

Unfortunately, we’re not in theoretical territory anymore. We no longer have to dig into paleoclimate records to imagine what a hotter Earth looks like.

We just have to scroll.

Because 2024 wasn’t just another chapter in the unfolding climate saga — it was the beginning of a cascade we were told to fear, then told to expect, and now have no choice but to survive.

The signs of collapse weren’t buried in data charts anymore — they screamed from headlines as communities buckled under a planetary endurance test against the “unprecedented,” the “uncharted,” and the “unpredictable” — relentless and unapologetic.

It started early, in my own Patagonian backyard, with heatwaves that cracked trees open like matchsticks. Then came the stories that used to live in the realm of dystopia. Penguin chicks leaping off Antarctic cliffs. Floods turning streets into rivers. The last glacier in Venezuela disappearing, like the last breath of a dying patient. Even the Arctic — a place that once held the cold like a sacred trust — turned on us, coughing carbon back into the air like a sickened lung.

Block by block, the Jenga tower of planetary stability is being pulled apart. You can almost hear the creak. How many more pieces before the whole thing crashes?

And yet, the list only kept growing.

Coral reefs bleached into oblivion, forests burned, winds and currents became erratic, ice caps melted, and biodiversity hit a new low. Even the myth of “climate havens” collapsed under hurricane-force winds and deadly floods.

Even the simple pleasure of food turned sour — search climate change alongside your favorite food, and you’ll see how climate change now stalks our plates with every meal. And it’s getting worse by the tenth of a degree.

By year’s end, 2024 had seared its name into history not only as the hottest year on record — and likely at least 125,000 years — but as the first to breach the ominous 1.5ºC threshold and with seven of nine planetary boundaries crossed.

These have all become symbols of what many experts warn: that we are on the brink of entering an era where extinction is becoming the rule, not the exception, with a vast number of species poised to vanish in what could reshape Earth’s biological legacy forever.

The planet’s vital signs, measured not only in temperature but also in carbon dioxide, methane, and ice caps’ minimum extents, only keep climbing like a patient who is about to go into cardiac arrest.

And the first quarter of 2025 is only accelerating this dangerous trend.

From Warning Shot to Reckoning

Back in January, scientists were counting on a cooling La Niña to bring some relief, nudging global temps back down from El Niño’s red zone. That didn’t happen. Instead, global temperatures stayed brutally high, shrugging off natural variability like a fever that no longer responds to ice baths. The Earth, it seems, is no longer playing by the rules we thought we knew.

January 2025? The hottest ever recorded.

February? Third hottest.

March? Tied with 2016 — the previous El Niño kingpin — for second place.

April? Second-hottest ever at 1.51°C above pre-industrial levels, marking the 21st out of the past 22 months to blast past that critical 1.5°C line — nearly two straight years over a threshold that was held as the ultimate warning sign.

2025 has kicked off as the second warmest start to any year in recorded history, extending a remarkable run of exceptional warmth that began in July 2023.

And it’s not just heat. It’s ice, too — or rather, the lack of it. Between January and March, the Arctic hit record-low winter sea ice, while Antarctica logged its second-lowest summer minimum. Combine them and you get the lowest global sea ice coverage ever recorded. The planetary air conditioner failing on a planetary scale.

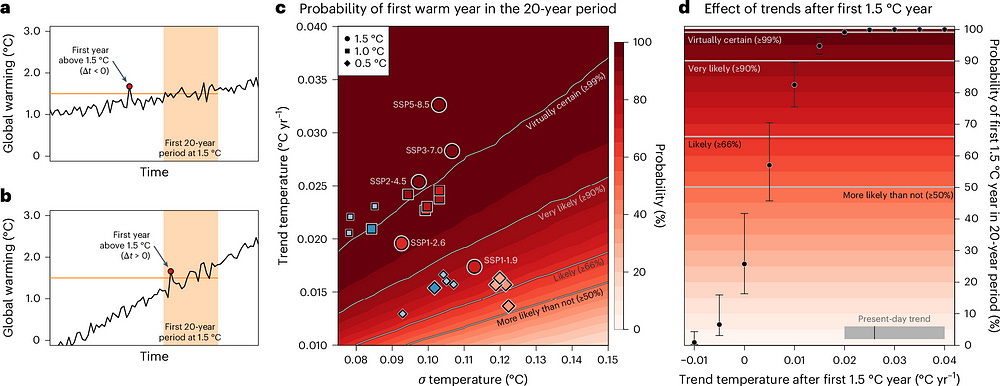

According to Berkeley Earth, there’s now a 1 in 5 chance that 2025 will dethrone 2024 as the hottest year ever recorded, a 53% chance of taking second place, and a 52% chance it stays above 1.5°C for the full year.

What happens next depends largely on whether the Pacific wakes up with another El Niño or La Niña. But if the past two years taught us anything, it’s that climate models built on historic behavior are struggling to keep up with a system that’s gone rogue.

And no — crossing 1.5°C in a single year doesn’t breach the Paris Agreement’s goals, not technically. The target is based on 20-year averages exceeding a pre-industrial baseline, not monthly heat spikes. But let’s be honest: this is like arguing over definitions while your house is already on fire. Every year above that line pushes us closer to a future we can’t come back from.

In fact, a recent study warned that three individual years above 1.5°C — not decades, just three — could signal the effective death of the Paris target. Similarly, another paper found that 12 consecutive months above that threshold gives us an 80% chance that long-term warming of 1.5°C has already been reached.

Short of a giant volcanic eruption blotting out the sun, or an equally massive global climate effort, we are spiraling toward a point of no return.

So, if you’re still clinging to the idea that 1.5°C is a future threat, look again: we may already be past it.

The Age of Overshoot: Why Every Fraction of a Degree Matters

Overshooting 1.5°C is the road we’re already barreling down. The Paris Agreement’s long-term goal was to hold the line. Instead, we’re preparing to blow past it, and then pray we can claw our way back by somehow vacuuming CO₂ out of the sky.

But let’s be brutally honest: overshoot isn’t just a technical hiccup. It’s a “we’ll-fix-it-later” fantasy that ignores how ecosystems unravel, how glaciers don’t grow back on command, how coral reefs won’t regenerate in boiling oceans, and how crop failures, coastlines, and collapsing health systems don’t just bounce back once the thermometer dips — if that ever happens during our timeline.

Reversing an overshoot could take the better part of a century. In human terms, that’s three generations raised under escalating chaos before the climate even begins to stabilize.

And the PROVIDE project — backed by Horizon Europe — is opening a window into that near-future world: heat-stressed cities, dying ecosystems, and impossible choices. It offers tools for the public to visualize what’s at stake, making climate risk painfully tangible, and showing how today’s decisions backfire into tomorrow’s suffering.

So let’s talk about heat. Not the gentle kind — the kind that kills.

Imagine you’re sweating on a hot, humid day. Normally, sweat evaporates and cools you down. But if the air is both too hot and too humid, sweat can’t evaporate as easily, making it feel even hotter.

You stay hot, no matter what.

Wet bulb temperature measures the lowest temperature air can reach through evaporation (like how sweat cools you). It’s called “wet bulb” because it’s measured by wrapping a wet cloth around a thermometer — the evaporation cools it down, just like sweat cools your skin.

Chennai, India, is one of 140 cities where PROVIDE modeled urban heat stress risks. Under our current track — about 2.7–3°C by 2100 — the number of days when wet-bulb temperature exceeds 31°C would jump to 180 per year. That’s nearly half the calendar under extreme heat stress, brushing up against the edge of human survivability. In that world, going outside wouldn’t just be uncomfortable. It would be life-threatening, with a high risk of heatstroke, organ failure, or death if exposed too long. Like walking into an oven with no off-switch.

Choose another path — a 1.5°C low-overshoot scenario — and heat stress days could peak around 120 by mid-century, then drop to about 110 by 2100. Still brutal, but the difference between a challenging future and an unlivable one.

Even if we manage to cool the planet later, the aftershocks will keep rolling for centuries as our climate slowly, painfully adjusts to a new equilibrium for decades, if not centuries.

Because Earth’s climate is like a massive ship — it turns slowly, but once it starts turning, it’s hard to stop the inertia. There’s a lag effect between our actions and their consequences. When you step into 2025’s weather, you’re actually experiencing the aftermath of a 350–370 ppm world. The real impact of today’s 430 ppm CO₂ world is still loading.

And we are not stopping here.

Even in the best-case scenarios, where we manage to limit CO₂ emissions, we’re still projected to peak around 550 ppm. That’s like triggering two ice ages in reverse, faster than the Great Dying — the worst mass extinction Earth has ever seen. What took nature millions of years, we’re doing in a couple of centuries.

And then there are the tipping points that could push us much further. Scientists now believe we’re locked into at least 2.5°C of warming. Pass enough tipping points, and we’re looking at 4–5°C on a fundamentally altered planet.

So when someone shrugs and says, “It’s just a little warmer,” remind them of their own misery during that last fevered night.

Still think a fraction of a degree doesn’t matter?

To Be The Compounding Marginal Change

This isn’t theoretical. This isn’t just “for our children.” This is right now. This is us. My generation. Your generation. Ovens in the sand. Hospitals packed with heatstroke victims. Insurance companies pulling out of entire coastlines. Coral turning into bone yards. Whole ecosystems — entire ways of life — already tipping past the point of no return.

The science is no longer screaming — it’s sobbing. One in four people born today will endure record-shattering extremes every single year of their lives. We are entering a world where “unprecedented” becomes the new baseline. Where the average child will be cooked, flooded, smoked, and displaced more times than their grandparents ever dreamed possible, all because fossil fuel combustion rewrote the atmosphere.

And yet, political leaders will still pass the buck. Oil companies will still rake in record profits while lobbying to water down the very targets they helped set. Carbon offset schemes will turn into the latest shell game, and promises made at summits will vanish like melting glaciers.

It’s easy to feel paralyzed in the face of such devastation, but despair and defeat cannot be a strategy. Yes, our planet’s health is well outside the safe operating space for humanity. Yes, the cascading effects of human impacts are accelerating. But no, this doesn’t mean we’re powerless.

So the question isn’t whether we can change the establishment. The question is whether we own this moment.

I’m not here to hand you hope wrapped in recycled paper. I’m here to tell you that every fraction of a degree still matters. That your voice — yes, yours — can pressure a city council, push a newsroom to cover the story, force a company to change. That swapping your car for public transport or planting trees in an urban jungle can be radical. That getting your hands dirty in a community orchard or diving into the ocean to reforest a coral garden might just be your calling. In all, that refusing to look away is itself an act of resistance.

The heat will be merciless.

The turtles won’t save themselves. Neither will the reefs. Or the crops. Or the babies born into heat domes that stretch for weeks, swallowing entire harvests, cities, and futures.

But we can.

Because to be alive right now is not just to witness the collapse. It’s to embrace it, so we can be the compounding marginal change — just like that fraction of a degree that changes everything.

All the current political uproar is a form of necessary healing as the body politic fights off the right-wing infection. But isn't it essential for us to remember that it means very little to restore democracy if the cost is a dying planet? It's a multi-front war we are now engaged in. Thank you Ricky for continuing to remind us of the environmental battles we must continue to our energy into.

Yes. Messing up our Goldilocks Zone. Why change the orbit of your planet when you can bump up a trace greenhouse gas level? How much to collapse civilization? How much to eliminate our species? Our propensity to kill one another and our possession of nukes are the ultimate force multipliers for climate change extinction.