Penguins Are Literally Crapping Out Climate Resilience

Cloudmakers in tuxedos: because climate isn’t just physics — it’s biology and interaction

You don’t forget the smell.

I first met it in Patagonia, years ago, standing on the pebble beaches of Península Valdés, where hundreds of thousands of Magellanic penguins come to breed each summer. That guano stench is a permanent part of the landscape — sharp, sour, gut-wrenching. It clings to your nostrils like Velcro and stains the back of your throat with something both dead and alive, like the Earth itself is rotting.

But I never thought that same stench might be holding Antarctica together.

Months ago, we witnessed a surreal diving competition: hundreds of juvenile emperor penguins, huddled on the lip of a 50-foot ice cliff, driven by hunger and instinct. How do we get down there? — they seem to ask each other, closer to the abyss. Until one brave chick takes the first plunge. Then another. And so, like dominoes in down jackets, they tumble into the sea below, using their swimming wings to break their fall. It is clumsy, desperate, and fascinating.

But this isn’t some wildlife blooper reel. This is a splashy show of the climate crisis that marked yet another year of record Antarctic heat, disappearing sea ice, and ecological breakdown that’s now bleeding into 2025.

And yet… what matters as much as how these penguins get down there is what they leave behind. Is it fear? Maybe. Is it love? Possibly. But it’s definitely ammonia.

Because millions of these birds eat and breed in colonies, and their guano, thanks to a fish-and-krill-rich diet, is packed with nitrogen waste that breaks down into ammonia gas. And according to a new study, that noxious gas doesn’t just reek — it’s a bizarre climate infrastructure bringing resilience to the edge of the world.

Sometimes, Earth’s wildest systems are held together by the most unlikely threads.

Guano In The Clouds

At first glance, the idea that penguin poop might cool Antarctica sounds like a children’s book twist. But their guano isn’t just a mess on the ice.

In nature, living organisms shape the air we breathe and the climate we live in. They do this through a variety of mechanisms, including the emission of vapors that affect cloud formation by creating cloud-seeding particles called cloud condensation nuclei, which impact Earth’s surface radiative balance, precipitation, and weather. Forests emit organic vapors. Industries and vehicles release them as pollutants. And in pristine marine and polar environments like Antarctica, where trees and vegetation are scarce, the aerosols from penguin guano and marine phytoplankton play an outsized role.

So, when penguins come ashore each summer, they aren’t just waddling toward nesting sites. They’re fertilizing vast swaths of land with a nitrogen-rich cocktail of droppings. That guano emits ammonia, which escapes into the air and binds to sulfuric acid — a by-product of dimethyl sulfide released by phytoplankton — like a fuse meeting flame, triggering new particle formation events: the invisible scaffolds on which clouds are built.

And in this remoteness, where smokestacks and cars don’t interfere, they operate in a near-preindustrial atmosphere where every particle counts. Even a few hundred parts per trillion of ammonia can shift cloud dynamics. Which is why penguin colonies matter. A lot.

During the austral summer of 2023, researchers set up atmospheric detectors around the Argentine Marambio Base and near a massive Adélie penguin colony, roughly eight kilometers (five miles) away. When the wind turned toward the instruments, ammonia concentrations spiked — up to 1,000 times higher than the baseline levels.

Even after the 60,000 birds abandoned their nests and vanished into the sea, the guano kept working, releasing ammonia for at least a month. The land stayed chemically alive.

That’s not a fart in the wind

Although the research team didn’t quantify that climate effect, which would require further research, that pungent scent, those foul-smelling fumes, kick off an atmospheric chain reaction that may be helping cool Antarctica. A feedback loop, caught in the act.

That sulfuric acid–ammonia bond isn’t just a fluke, but it only works if the ammonia’s there. And in most of Antarctica, it isn’t — unless penguins show up and drop their payload.

Other chemicals are in play. Iodine compounds from the sea ice. Amines from microbial communities. Each interaction nudges the system further, sometimes accelerating cloud formation, other times dimming its effects.

The chemistry is complex. The takeaway is not.

Changes in biodiversity are changes in climate. Penguins aren’t just cute faces for conservation posters. They’re engineers in the atmospheric machine. And they are, quite literally, crapping out climate resilience.

A better understanding of this dynamic could help scientists refine their models of how Antarctica will transform as the world warms and investigate, for instance, if some penguin species produce more ammonia and, therefore, have a greater cooling effect.

But this is not some magical adaptation. It’s a fragile, localized, and seasonal gift of ecological coincidence — one that depends entirely on the survival of these colonies, and the ecosystems they anchor. You lose them, you lose the shield. You lose a tiny but essential valve in Earth’s climate system.

And, like the ice, penguins are disappearing off the cliffs.

Climate Workers Getting Laid Off Mid-Shift

Climate change is a cumulative problem that knows no geographical, political, or societal limits. In a world where the consequences of global warming are felt everywhere, Antarctica, often considered remote and distant, is now bearing witness to an undeniable footprint.

Scientists have long speculated that polar regions would warm faster than the rest of the planet, a phenomenon known as polar amplification. While this has been observed in the Arctic, which has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average over the past four decades, the South Pole remained an enigma.

A study of ice core records found that Antarctica is likely warming at almost twice the rate of the rest of the world, much faster than models predicted. This has potentially far-reaching implications, from global sea level rise to wildlife ecosystem alterations.

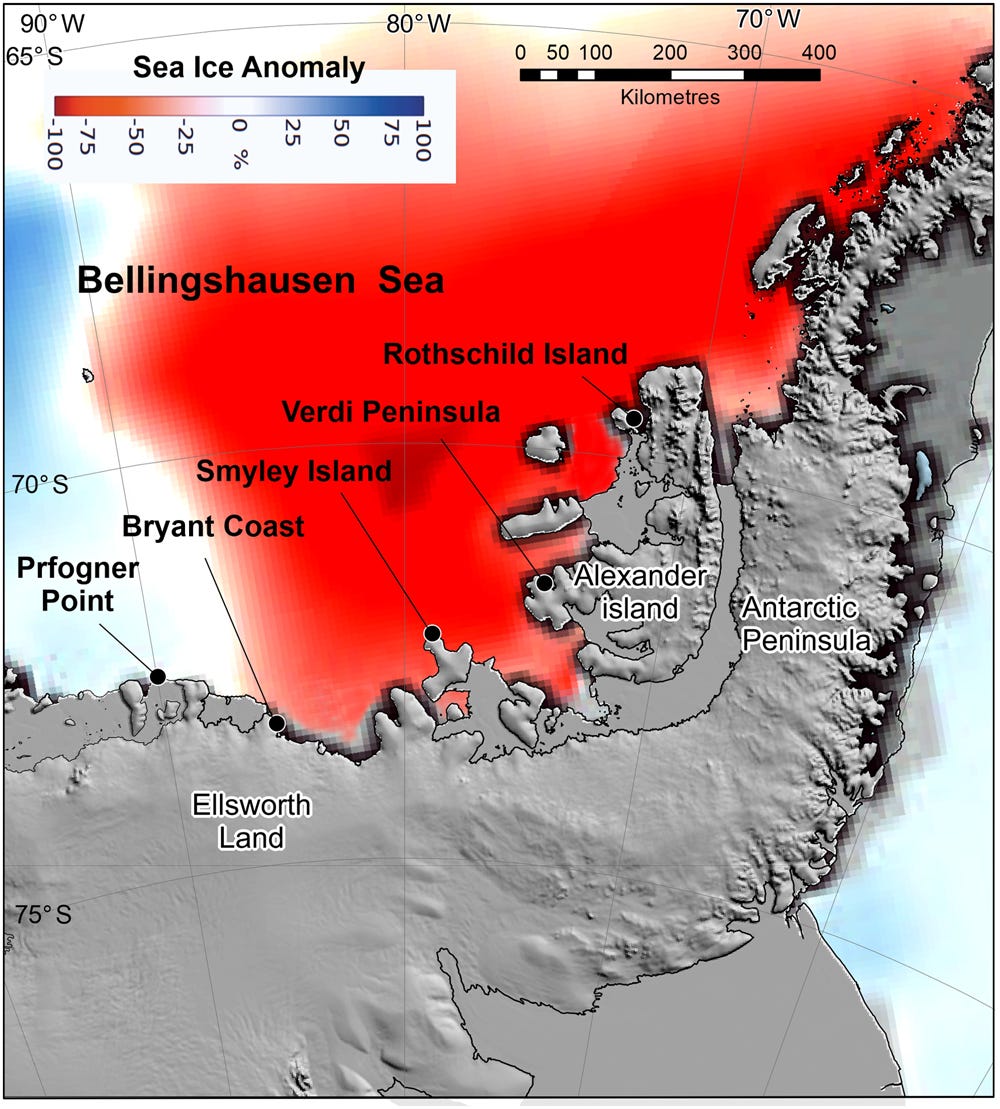

It is already understood that widespread loss of sea ice extent threatens the habitat, food sources, and breeding behavior of most penguin species that inhabit Antarctica. But nothing like the unprecedented event that unfolded in the Bellingshausen Sea, marking the first time multiple colonies across a vast region simultaneously failed to breed. Analysis of satellite images showed the breakup of usually stable sea ice, and many parts had near-total loss. This led to the disappearance of the colonies, with an estimated 7,000 chicks dead: if they dived in water, like those jumping off ice-cliffs, they drowned because they weren’t ready to swim; if they got back onto the ice, they froze because they didn’t have their waterproof feathers at that stage.

Penguins are climate refugees in their own frozen home. Their populations are already declining. About 30% of the known 62 emperor penguin colonies in Antarctica have been affected by partial or total sea ice loss since 2018. Warming is considered their main long-term threat, with projections that by 2100, about 90% of colonies could be so small that they are essentially extinct.

Because, as warming melts sea ice and acidifies oceans, krill — those tiny, shrimp-like crustaceans that anchor the Antarctic food web — are vanishing. Fewer krill means less food. Less food means fewer chicks. Fewer chicks mean fewer guano piles. And fewer guano piles, fewer clouds — which means more warming and more disruptions to the animals, and on and on in a self-reinforcing feedback cycle.

These aren’t just animals in trouble — they’re climate workers getting laid off mid-shift after we realized they had a critical job.

We Don’t Need More Innovation — We Need Less Interference

There’s something humbling about this: that a creature so often reduced to a cartoon can wield atmospheric influence through something as mundane as excrement. But in Antarctica, nothing is isolated. Every living thing — every breath, every drop, every waddle — feeds into a web of connection more intricate than anything we’ve built.

That’s why this story isn’t just about penguins or poop or clouds. It’s about the blind spots we carry when we talk about climate in silos. It’s about realizing that resilience doesn’t come from high-tech fixes or distant summits — but from letting ecological relationships flourish, uninterrupted.

We like to think of climate change in compartments. Carbon in the atmosphere. Melting glaciers. Rising seas. Dying reefs. As if each crisis were a separate news story. As if penguins and particulate matter belonged in different worlds. As if what happens on the edge of Antarctica doesn’t spill into our lungs, our crops, our economies.

But the Earth doesn’t recognize our categories. The planet operates in subtler currencies: in feedback loops, not press releases. Cause and effect. Chick and cloud. Guano and cooling.

And so we keep looking for solutions at the top, in policy summits and carbon markets, in emissions curves and transition minerals, that we’ve missed the actual fabric of the Earth unraveling under our feet. The climate isn’t just physics. It’s biology. It’s interaction.

We don’t need more innovation. We need less interference.

And maybe the most radical climate solution left is to let shit fall where it’s meant to fall — and leave it the hell alone.

So be loud.

Great article.