Saúl v. Goliath: A Case That May Become the Climate Fight’s Tipping Point

The Peruvian farmer who put the fossil fuel industry on trial

The lake is still. Too still. A turquoise mirror high in the Andes, fringed by the broken teeth of melting glaciers. But beneath that surface, the water is rising — not just in volume, but in pressure. If it breaks, it won’t knock. It will roar.

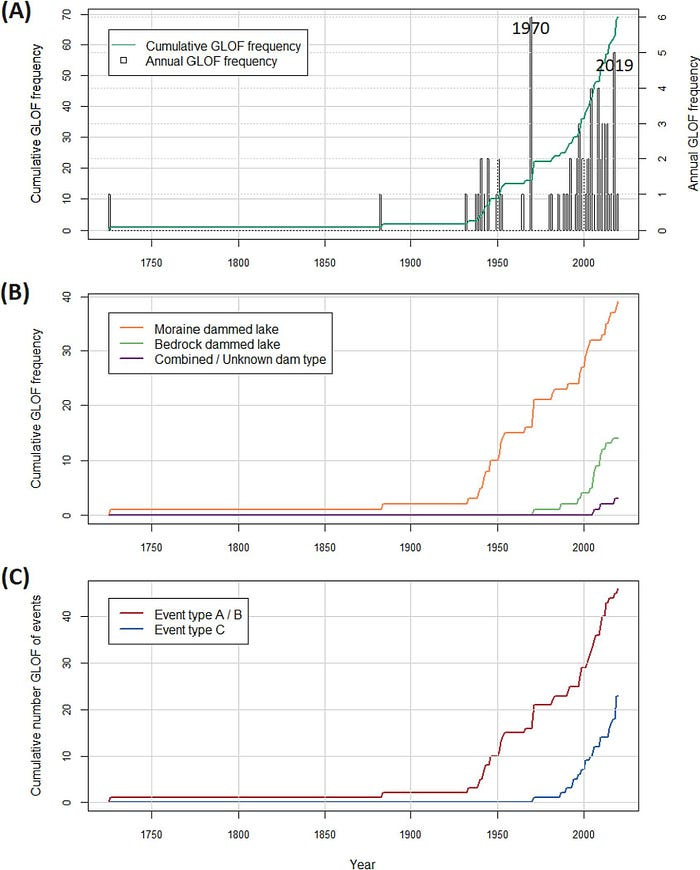

Saúl Ananías Luciano Lliuya has lived under that threat most of his 45 years of life. A mountain guide, farmer, and father, he tills the same soil his ancestors did above Huaraz, Peru — a town of over 50,000 cradled below Lake Palcacocha, a glacial basin swollen to thirty times its 1970s size. In 1941, the lake burst and wiped out a third of the town, killing more than 1,800 people. Since then, the mountains have warmed, the glaciers have thinned, and the flood maps have redrawn themselves closer to Saúl’s doorstep.

But this isn’t just a story of meltwater and memory. It’s a story of responsibility — how far it travels, and who it eventually lands on.

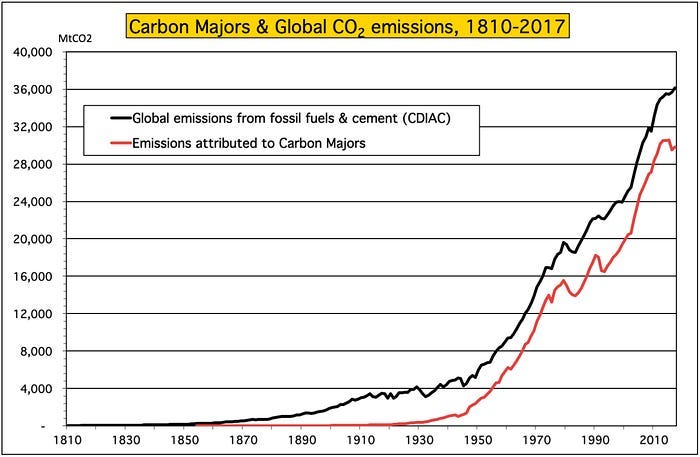

In November 2015, Lliuya did something no Andean farmer had ever done: he took the fossil fuel industry to court. Backed by the NGO Germanwatch and legal support from Stiftung Zukunftsfähigkeit, he filed suit in Germany against RWE, the country’s largest electricity producer. The claim was that RWE’s historic greenhouse gas emissions — responsible for approximately 0.47% of global carbon output at the start of the proceedings and 0.38% at the concluding stages, according to the Carbon Majors Study — had helped fuel the retreat of the glaciers above Huaraz, and with them, the rising threat of flood to his community. That RWE, therefore, owed $17,500, their proportional share of a $3.5 million glacial flood defense system.

The case, Saúl Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG, was unlike any climate lawsuit the world had seen. This wasn’t a regulatory slap on the wrist, or an administrative review over emissions targets. This was civil litigation built on old, surprisingly simple and almost pre-industrial bones: nuisance law. If your neighbor’s actions impair your property, you can ask them to stop — or pay.

Think of this case like a groundbreaking twist on an age-old principle. Instead of suing your neighbor because their tree roots damaged your foundation, Lluiya sued the German energy giant because their carbon emissions melted glaciers, threatening his home.

It was like saying: “Your factory in Germany is making my home in Peru unsafe, and even though we’re thousands of miles apart, we’re still ‘neighbors’ in the global sense.”

The revolutionary part was applying this traditional legal concept to climate change, creating a direct link between a specific emitter and a specific climate impact.

This wasn’t about regulations or emission targets — it was personal. It asked: “Your business decisions are threatening my home, so shouldn’t you help pay to protect it?”

And for the first time, a court didn’t laugh. It listened.

Over the next decade, the case crawled through the German court system, from the Regional Court of Essen to the Higher Regional Court of Hamm. Evidence was submitted. Climate models were debated. Attribution science — once theoretical — was brought into the courtroom. While climate litigation had mostly targeted governments for inaction (as in Urgenda v. The Netherlands), this was a private suit against a single corporate emitter for damages.

And for a moment, it looked like it could succeed.

The First Wall — and the First Crack

When Saúl Luciano Lliuya v. RWE AG first landed in the courtroom of the Regional Court of Essen, it didn’t shake the foundations. Not yet.

The judges dismissed it. Too complex, they said. Too far-fetched. They ruled that RWE’s emissions — though substantial — couldn’t be tied in a “linear causal chain” to a specific risk in the Andes. The court argued it couldn’t offer “effective redress” because, even if RWE stopped emitting tomorrow, it wouldn’t drain the lake hovering above Huaraz.

In legal terms: case closed.

In planetary terms: justice denied.

But Lliuya didn’t stop there. In early 2017, he appealed the decision. And this time, a different court (with a different lens) answered.

On November 30, 2017, the Higher Regional Court of Hamm cracked the surface of climate law wide open. It ruled that the case was “well-pled and admissible.” For the first time in European history, a court acknowledged that a private fossil fuel company — not a government, not an abstract entity — could, in principle, be held liable for climate damages caused by its historic greenhouse gas emissions. The case was cleared for the evidentiary phase.

This meant that the court saw legal grounds to explore two questions:

Was there a real and imminent risk to Saúl’s home due to flooding from Lake Palcacocha?

And if so — was RWE partially responsible?

By invoking Section 1004 of the German Civil Code, the court didn’t just consider whether Lliuya had been harmed. It considered whether that harm was traceable to one specific emitter, whose industrial decisions in Europe could ripple into physical threats across the world.

For years, climate lawsuits had piled up in courts around the world. But most had been dismissed before reaching this stage, especially those aiming to hold companies — not governments — accountable. The Lliuya case was the first of its kind to reach evidentiary review. A peasant farmer from the Andes had forced one of the world’s largest emitters into a courtroom, under oath, to face the consequences of its carbon.

Then the waiting began.

Ten years. That’s how long it would take for the courts to reach a final ruling. Long enough for more glaciers to vanish. Long enough for a child in Huaraz to grow into an adult under the shadow of a swelling lake. Long enough for wildfires to rage across continents, for emissions to spike again, for fossil fuel executives to testify before parliaments and deny everything.

But the legal ground was no longer frozen. The thaw had begun.

The Verdict: A Door Opens, Even as It Closes

By the time the judges arrived in Huaraz, the ice had already told its part of the story.

In May 2022, after pandemic delays and years of legal grind, the judges of the Higher Regional Court of Hamm, flanked by court-appointed experts and legal teams, traveled over 10,000 kilometers from Germany to the Andean city. Their task was to see with their own eyes whether the melting lake above the city posed a real and imminent threat to Saúl Luciano Lliuya’s home.

Three years later, on May 28, 2025, the verdict came down.

And it came down hard.

The court ruled against Lliuya. Based on extensive technical evidence, it found that the risk of flooding to his specific property was too remote to justify compensation. The probability that water from Lake Palcacocha would reach his doorstep within the next 30 years was pegged at just one percent. And even if it did, the projected surge would barely scuff the foundation — mere centimeters of water moving too slowly to tear through stone.

Case dismissed.

On paper, he lost. But beneath that thin layer of legal language, something far bigger shifted.

Because while the court rejected the factual basis for Saúl’s personal damages claim, it did something no other court in the world had yet done: it affirmed the legal principle that a single corporate emitter — even one an ocean away — could, in theory, be held liable for climate damages caused by its emissions. Not a government. Not an abstract system. A company. A name.

The court didn’t flinch at the geographical gap between RWE’s coal plants in Germany and a glacier lake in Peru. It rejected the idea that distance cancels responsibility. It also cut through the usual corporate smokescreens: No, this ruling wouldn’t trigger a cascade of lawsuits against individual citizens. No, this wasn’t about punishing people for existing. This was about scale. About power. About industrial responsibility.

The judges were clear: If the risk to Lliuya’s home had been more direct — more immediate — RWE could have been forced to pay. Not out of charity. Out of obligation.

That legal reasoning may sound clinical. But in the context of global climate litigation, it’s nothing short of revolutionary. It breathes life into the principle long chanted by activists and communities but rarely enforced in court: polluter pays.

RWE and major polluters didn’t walk away unscathed. They walked away exposed. This ruling could light the fuse on litigation that holds the most untouchable-seeming businesses to account for their climate destruction.

And now, every fossil fuel giant, every utility, every multinational watching from behind mirrored glass conference rooms has to ask: What if the next Saúl wins?

It’s like fossil fuel companies have been speeding on the highway for decades, and now the first police car has turned on its lights. They haven’t been pulled over yet, but the precedent is set — those flashing lights in the rearview mirror signal that accountability is getting closer.

The Lawsuit That Changed the Climate Fight Forever

The first time I read about the case, I couldn’t make sense of it.

A Peruvian farmer filing a lawsuit against a German energy giant whose closest operation was more than 2,000 kilometers away from his hometown, claiming that RWE should contribute to flood protection measures at his property situated below a glacial lake in the Andes due to increased flood risk induced by climate change? All for $17,500 in a $3.5 million project?

The whole thing sounded like a strange parable — or a publicity stunt. The German electricity company is one of the world’s biggest greenhouse gas polluters, but has never operated in Peru. I squinted at the headlines, hunting for a missing link: The farmer is an opportunistic bounty hunter? The energy company operates under a different name in his town? Is Lliuya backed by some hidden corporate rival? Who is really behind this?

And yet, the more I read, the more it clicked.

Saúl, of course, wasn’t alone. It was clear that Mr. Lliuya wasn’t operating all by himself. I’m not saying that it wasn’t his idea to start the litigation against a mass-polluting company. But it is no coincidence that the claim was strategically supported by an environmental NGO, Germanwatch, and with legal support from Stiftung Zukunftsfähigkeit, and the amount of damages being sought was relatively small compared to the precedential and publicity value of the claim.

He was the front line of something the fossil fuel industry had been dreading for years: individual accountability. So we didn’t know it, but most of us were there with him, too.

This wasn’t about abstract climate targets or government inaction. This was about naming names. This was about putting a corporate carbon footprint on the witness stand. It was about asking a question the world has avoided for decades: If your emissions helped melt my mountain, shouldn’t you help pay to protect my home?

The courts in Germany said no — this time. That the threat was too slow, too soft, too far away.

But in the same breath, they said something else.

They said that if the risk had been higher, then yes, RWE could’ve been held liable. A company, not a country. Polluter pays, in real legal terms, is now a possibility.

And that changed everything. Because now, the blueprint exists.

It is a milestone in what some legal scholars call “strategic litigation.” This is the use of the legal system not just to win individual cases, but to influence policy, raise awareness, and build momentum for broader change.

Think of it like planting a flag on a mountain. This case wasn’t about winning money from RWE — it was about using the courtroom as a stage to tell a bigger story. Even though Saúl didn’t win his specific case, he helped change how we think about who’s responsible for climate damage. It’s like losing a battle but setting the stage to win the war.

Climate attribution science — once too blurry to hold up in court — has become sharp enough to cut through decades of denial. Carbon Majors, once hidden behind denial and legal firewalls, are being named and sued.

And Saúl isn’t the only one knocking on the courtroom door. In Switzerland, Indonesian islanders are suing a cement company. In Belgium, a farmer is going after TotalEnergies. In Montana, teenagers dragged their state to court — and won.

The Lliuya v. RWE decision might not have delivered immediate justice. But it redrew the battlefield. It told every oil executive, cement magnate, and coal baron that distance is no longer a defense. That the climate is a crime scene — and names are starting to be written down.

It also forced a reckoning: If courts are beginning to acknowledge these links, why aren’t lawmakers acting faster? Why are fossil fuel companies still drafting glossy decarbonization plans while expanding their extraction projects? Why are climate disclosure laws still toothless in countries like Canada?

This lawsuit didn’t just expose one company — in fact, RWE was just a fuse. It exposed, once again but from a new scope, a system where the poorest pay for the carbon burned by the richest. Where Andean farmers watch their lakes swell while European utilities cash dividends.

And Saúl knew that. He knew he wasn’t going to bring RWE to its knees. But that was never the point.

The point was to make the world look.

To make the judges stand on his soil. To make the engineers map the melt. To force them to connect two dots that had always been drawn apart: cause and effect.

The case was always beyond a lake. It was a case about proximity, even if 10,000 kilometers away. Between an emission and a disaster. A profit and a consequence.

And now that connection has been etched into legal precedent.

Even in losing, Saúl Luciano Lliuya made history. His was the first climate lawsuit to reach an evidentiary stage against a private company. And he did it not with power or money or influence, but with a sense of duty — for his community, and for the future his children will inherit.

Today, he continues his work with Wayintsik-Perú, helping farmers adapt to a climate they didn’t cause. Teaching them not just how to survive the floods, but how to fight for what’s fair.

Because this isn’t over. Somewhere, the next Saúl is already watching the ice melt. Not just as a witness. But as a plaintiff.

This was just the beginning — a tipping point in climate justice.

May the northern lights guide you,

M.

I agree with Marlena. Thanks for reporting this Ricky.

This is very good news.