The Decline of Genius: Where Did All the World-Changers Go?

We didn’t just stop making Einsteins — we built a system designed to make sure they never showed up

I’ve spent hours eavesdropping on strangers’ screens. I use a lot of public transportation, and those places are tight enough that looking over your shoulder is easier to hide; if you have a wide eye range, you don’t even need to turn your head. So, like everyone out there, sometimes, I just can’t help it — even when all I ever see is the same.

Everyone’s scrolling. Clicking. Searching.

Consuming reels, tutorials, subreddits, music, podcasts… dopamine.

And I can’t help but think the most depressing fact about humanity today isn’t war or greed or collapse. It’s this: billions were handed near-limitless access to knowledge — and instead of lighting up the world, we got TikTok filters and ChatGPT homework hacks.

For a moment, think of what should’ve happened. Not in theory, but in reality. With the internet pouring open, with populations booming, mass education expanding, malnutrition falling, barriers cracking — gender, race, geography — and nearly all human ideas indexed, translated, and searchable, we weren’t just poised for a golden age.

If genius were just a matter of talent plus access, this should have triggered an explosion of world-class minds. Not just a few gifted outliers. But a sustained flood of paradigm-breakers. Think: more Ramanujans, more Newtons, more Sigmund Freuds. More people remaking how we think about time, language, biology, power.

We were standing at the gates.

Instead, everything, even our thinking, has dulled down.

A flattened culture. Uniformity dressed up as innovation. Thought leaders going viral, not deep.

Eavesdrop long enough during a slower-than-usual, tight-as-expected bus ride, and you start asking: if everyone’s got the tools of a genius at their fingertips now, why has this real-world experiment seen not just no effect, but seemingly the opposite — a decline in genius? Shouldn’t we have seen at least a small uptick?

Every human alive today can summon more information in one second than Einstein could in a lifetime. And yet… where are the 21st-century Einsteins? The world-historic intellects who don’t just participate in a field, but detonate it?

That’s how rare true world-historic geniuses are nowadays, and how different it was in the past. In sports, we see disruptive figures like Michael Jordan, Lionel Messi, Usain Bolt, Simone Biles appear every decade. In science and the arts, that doesn’t seem to be the trend. The human body keeps improving and reaching new heights, but the mind is stagnating.

In Oswald Spengler’s 1914 Decline of the West, he names Tolstoy, Nietzsche, Marx, Dostoevsky, and Darwin not just as brilliant, but as civilizational anchors immediately recognized as world-historical figures. Tolstoy was only four years dead and Marx, only 30, when Spengler started his book. You didn’t need to argue their importance. It was obvious — you already felt it in your bones.

Can you name a single person who died in the last decade you’d say that about? How about the last two? Three?

Or anyone still alive who is shaping a global worldview?

If you’re still reading, you probably feel what I’m circling around. Not just disappointment, but the eerie sense that something deeper is broken.

What happens to a civilization that forgets how to think new thoughts?

Look, I get it if you’re skeptical. Measuring something like “genius” isn’t exactly straightforward — it’s like trying to measure how funny a joke is. It’s extremely hard to quantify, everyone has their own definition, and there’s always room for debate.

But when we look at the actual data, the trend is pretty clear:

This system is designed to break the genius inside you.

The Peer-Reviewed Reality

Isaac Newton once wrote to fellow scientist Robert Hooke in 1675, saying, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” But today we’re not standing — we’re stacking. Neatly. Predictably. And very, very carefully.

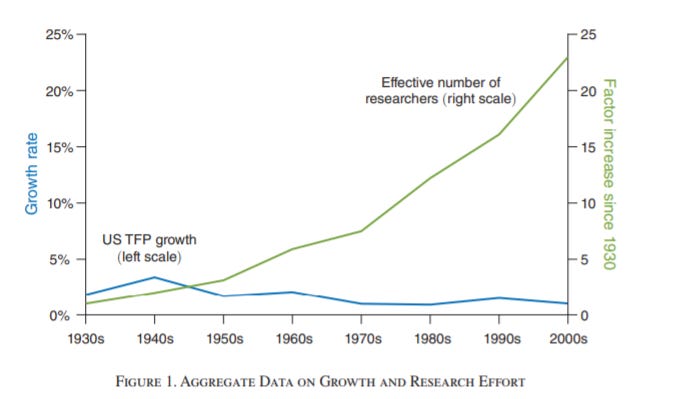

We are publishing more papers than ever. Budgets have swollen elevenfold since the 1950s. From a distance, it looks like an age of abundance. And yet, fewer of these breakthroughs are actually… breaking through.

After analyzing 45 million papers and nearly 4 million patents across six decades, a landmark 2023 study confirmed what many have sensed: science is indeed becoming less disruptive. The fire is still burning, but there are less radical ideas that smash the old world open and create entirely new fields.

Scientists used to invent new blocks — new ways of seeing, doing, thinking. Now, most are just recombining the same pieces in slightly more optimized patterns. Same bricks. Slightly shinier walls.

Breakthroughs are being replaced by tweaks. Big leaps have shrunk into marginal gains. Sure, we’re building bigger towers, but we’re not creating many new types of blocks anymore.

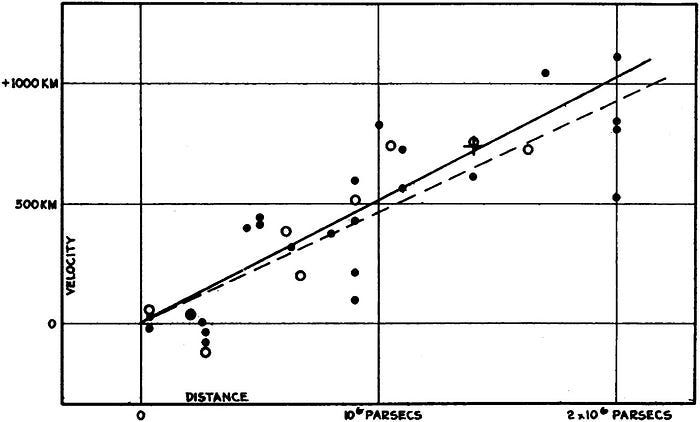

We even have a metric for this: the Consolidation-Disruption (CD) Index. In simple terms, if future work cites both a new paper and the old papers it builds on, it’s consolidating. But if it only cites the new paper — because that paper made the old ones irrelevant — that’s disruption, like Faraday’s electromagnetic induction or Hubble’s expanding universe.

The truly disruptive stuff is vanishing in a flood of filler.

Look at Watson and Crick. Or the first confirmed exoplanet. Those discoveries detonated old paradigms. But in a sea of scientific output today, even AlphaFold — the revolutionary AI system for protein folding — scored low on the CD Index because it didn’t erase what came before. It just improved it.

So, why did scientists stop building new blocks?

Start with this: the system doesn’t reward risk anymore. It rewards metrics. Most professors today spend under 20% of their time doing research. The rest is eaten alive by admin, grant-chasing, and the endless treadmill of publishing for the sake of citations.

Breakthroughs need time, space, and obsession. What they get is deadlines.

From 1996 to 2023, the number of papers per scientist doubled. But this wasn’t a renaissance. This was a mass-production line. Quantity won. Quality got buried. There’s no room for “A Beautiful Mind” in a world ruled by KPI spreadsheets. Papers are getting sliced thinner in a constant cycle of short-term thinking that does not tolerate slow, sometimes boring, sometimes weird work that lies outside the mainstream.

Like this, academia is gaming itself, relying on narrower slices of knowledge that benefit individual careers but not scientific progress more generally.

Some say the Einsteins are still here — they’re just quieter. That discovery is harder now. That the low-hanging fruits of scientific discovery have largely been plucked already, and that scientists nowadays need so much training (and money, of course) to reach the forefronts of their fields that they lose precious research time getting there. And there’s some truth in that. But if it were just about the old, “mature fields,” then new ones should still be exploding. They aren’t. Both old and new fields show the same trend — flatlining disruptiveness.

Which raises another possibility: maybe it’s not the fruit that’s gone. Maybe it’s the ladder that’s broken.

You can see this rot spreading beyond science. In music, song lyrics have become more repetitive. In literature, mainstream fiction often feels like it was written by an AI trained to avoid risk. Just go on social media, our supposed marketplace of creativity, for 5 minutes of conscious consuming, and you’ll see that everything looks the same.

Science isn’t an outlier of what happens when you optimize for attention instead of originality.

Sure, some argue that citation metrics are flawed. That innovation happens in waves. That we just don’t know how to measure genius properly. And to a degree, they’re right. But even after accounting for errors and adjusting for shifting norms, one thing stands: making big scientific discoveries is getting harder.

Take Moore’s Law. In the 1970s, a handful of researchers doubled the power of microchips every two years. Now, it takes 18 times more researchers to maintain that same pace.

The system is still climbing — but it’s exhausted, gasping, and bleeding funding to stay upright.

And we should be honest about what that means. The absence of genius is more than just a philosophical problem. It’s an existential one. Because when culture flattens, when institutions calcify, when thought stops moving, civilizations don’t just fall behind. They fall apart.

So, where are all the Einsteins and Beethovens?

The Answer Isn’t School

And if we look into research on different education strategies and their effectiveness, we do indeed see all sorts of debates about best practices, learning styles, class size, monetary policy, and equality. But mostly we see, actually, that none of it matters much.

If you’re still hoping the education system will save us — don’t. The data is not ambiguous. Winning a school lottery in the U.S., China, or Kenya? Doesn’t change outcomes. Private or public? Makes no meaningful difference once you control for class. That elite middle school in Shanghai or fancy prep academy in New York? Strip away the Harvard-style branding, and the results are eerily similar.

We’ve built a global machine around the illusion that better schools produce better minds. But what they’re actually producing — consistently, globally — is the same pattern of mediocrity, just in different uniforms.

Some take this as proof that intelligence is hardwired in. That maybe it’s all just IQ and genes. But that’s not quite it either. Because buried under all the noise, researchers have found one education method that does work. It’s not new. It’s not scalable. And it’s not fair.

It’s tutoring.

Not apps. Not AI. Not “flipped classrooms” or TED Talks on pedagogy. Just one person teaching another, one-on-one, consistently over time.

In the 1980s, educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom showed that “the average tutored student was above 98% of the students in the control class.” A full two standard deviations above conventional instruction.

This is what they call the “2-sigma problem” — not because it’s unsolved, but because the solution is too unequal to implement at scale.

Personalized attention works. But instead, we mostly use it to chase metrics in standardized tests — not to awaken minds, but to sharpen résumés and beat the SAT, ace APs, or game the GRE.

We’re not cultivating thinkers. We’re consolidating uniformity of thinking in a system that knows how to nurture genius, but only offers it to those who can pay for it — and even then, only in service of preserving the hierarchy.

Times of Tutoring and Generational Scaffolding

Once upon a time, tutoring wasn’t a side hustle for test prep. It was the full curriculum. And it was reserved for the ruling class.

Let’s call it what writer Eric Hoel does: aristocratic tutoring. Not SAT drills at Starbucks. Not tiger moms cushioning childhood. This was intellectual apprenticeship — one-on-one, immersive, and often round-the-clock. A time when a tutor was a fixture of the household. Scholar, guardian, provocateur. The relationship stretched across years, even decades. And while it was deeply effective, it was also deeply exclusionary. Education, like land or title, was inherited privilege reserved mostly for aristocrats.

The tradition runs as far back as history keeps records.

Marcus Aurelius, the philosopher-king, was shaped meticulously by an army of scholars. According to Will Durant, Marcus had seventeen tutors by adolescence — part mentorship, part emotional bond, all designed to mold an emperor’s mind.

Two thousand years later, the model hadn’t changed much. Bertrand Russell, towering genius of the 20th century, didn’t set foot in a school until he was sixteen. He was raised by wealthy grandparents and tutored by private intellectuals — one of whom had studied under Lord Kelvin.

Charles Darwin personally hired John Edmonstone, a Black freedman and former enslaved man, to tutor him in taxidermy when he was sixteen. Darwin wrote that Edmonstone “stuffed birds excellently” and was “a very pleasant and intelligent man.” Those lessons became foundational for Darwin’s specimen collection aboard the Beagle. A pivotal moment in scientific history began as a quiet tutoring session in a rented room.

Name a genius (or an aristocrat) and find a tutor. Descartes died of pneumonia after being summoned to tutor Queen Christina of Sweden at 5 a.m. in a freezing palace. Voltaire’s godfather tutored him; he, in turn, tutored Émilie du Châtelet, a mathematical prodigy. Ada Lovelace, considered the first computer programmer, was mentored by Mary Somerville — so respected that the gender-neutral word “scientist” was coined for her.

This isn’t about glamorizing the past. It’s about facing the truth of what has always worked — and who it has always worked for.

No case is clearer than John Stuart Mill. His father — famed utilitarian James Mill — decided to manufacture a genius from birth. Greek by age three. Latin by eight. Political economy, logic, and calculus by twelve. At fifteen, Mill began writing treatises on government and philosophy. He was supervised daily, never allowed to interact with other children.

It wasn’t nurture or nature. It was design. And the design was brutally effective.

You start to see the pattern. Virginia Woolf was rigorously homeschooled. Karl Marx’s father, wealthy and self-educated, tutored him personally. Hannah Arendt was taught by her mother and grandfather. You don’t need a data set to see how genius often runs in families, because what runs in families is more than genes. It’s structure. It’s time. It’s one-on-one intellectual labor. That’s what aristocratic tutoring is: generational scaffolding.

And it wasn’t just the formal tutors who mattered. It was older brothers, godparents, freedmen, revolutionaries, and philosophers — the entire orbit of a child’s mind shaped by adults who had the time, status, and stability to teach.

That’s the secret. Not magic. Not IQ.

Attention.

Who would’ve been Einstein?

When you think about genius, the name, the crazy hair, the tongue sticking out pop up immediately. Einstein. Who hasn’t heard someone sarcastically ask, Who do you think you are, Einstein? when they want to sound overly smart. And yet, the name alone feels like a counterargument. A lowly patent clerk who cracked the universe open. The man who turned time into something elastic. Proof, supposedly, that genius doesn’t need scaffolding — it just erupts. Uncontained, innate, and democratic.

Peel back the folklore and you find something less romantic.

The story that Einstein flunked school is mostly fabricated. Einstein had tutors early and often. His uncle Jakob, an engineer, coached him in algebra. A family friend named Max Talmud gave the 12-year-old Albert a geometry textbook and guided him through it week by week, igniting the spark that would one day bend spacetime.

These are the repeated patterns in the origin stories of disruptive minds. One-on-one intellectual intimacy. Adults with time and knowledge sitting down with curious kids, asking questions without rushing the clock.

You could dismiss it as a correlation. Aristocratic families could afford more leisure. But what if it was never solely about leisure, but also a style of education that has fallen out of favor?

When the aristocracy tumbled, so did its tutoring models — together with the slow vanishing of intellectual outliers over the 20th and 21st centuries. This decline of genius isn’t a mystery. It’s not that people are dumber. It’s that the pipeline has collapsed. The model that once nurtured the rarest minds — one-on-one, deeply human, radically personal — is gone because we’ve traded mentors for metrics.

We keep asking why there are no more Einsteins.

Maybe the better question is: Who would’ve been Einstein — if someone had just sat down and taught them?

The line factory of modern minds

We like to pretend education is fair. That it’s a meritocracy. That anyone with enough grit and flashcards can rise. Now, think about how the world runs most schools today — it’s like a big factory where every student is expected to learn the same way, at the same pace.

From kindergarten onwards, we put kids in boxes: “You’re a visual learner,” “You’re good at math,” “You need to sit still.” Instead of nurturing their unique interests, we make them follow a strict schedule and learn mostly from other kids who are just as new to everything as they are. Most students don’t meet a real expert in any field until college. And by then, they’re just one face in a crowd of hundreds. The system sequestered great minds from children.

We keep asking why we don’t see more brilliant minds emerging from our schools. But how can we expect extraordinary results from a system designed to make everyone average?

We’ve mistaken uniformity for equity. If kids fidget or can’t focus, there’s no asking — there’s medication.

And when tutoring does enter the picture, it’s not to accelerate a spark. It’s to patch up a failure.

Modern tutoring is remedial. A Band-Aid for broken report cards, forgotten algebra, and undiagnosed gaps. It’s applied reactively, like antibiotics. And it almost never reaches the kids who are doing well — because those are the ones we assume are “fine.” But that’s not how genius works.

Genius isn’t about fixing failure. It’s about feeding the fire before it dies out.

And yet the system does the opposite. It buries the flame under rubrics and pacing guides. It’s so focused on making sure everyone meets basic standards that it is actively hostile to the conditions genius needs to survive: time, trust, and attention.

By trying to teach everyone the same way, we’ve created a wall between young minds and the very people who could inspire them to greatness.

Will AI Help Create More Geniuses — or Finish the Job?

So, what if we could give every child their own personal Einstein-maker?

Recent studies show AI tutors can outperform traditional online instruction by a landslide — producing the same two-sigma effect once thought to belong only to flesh-and-blood tutors. A personalized, always-on Socrates in your pocket. That’s the pitch.

We’ve been here before. The internet was supposed to democratize brilliance. Instead, it became a firehose of distraction. Access to information didn’t produce a generation of polymaths — it produced screen fatigue and short attention spans.

Because brilliance isn’t built on access. It’s built on attention. On connection. On someone older and sharper taking your mind seriously before the world tells you not to bother. It’s about having someone who not only teaches you but also inspires you.

Think about young Einstein meeting Max Talmud, a human bridge between childhood wonder and the deep end of intellectual thought. A human connection that sparked something special.

You can’t automate that. Not yet. Maybe not ever.

Sure, you could technically hire a modern Max Talmud and treat education as craft, not consumption. Something closer to homeschooling, where parents ditch the factory model and go feral with intention.

But there’s an elephant in the room: good tutoring still carries the stink of money and elitism. So, as soon as it works, it will be called unfair.

Even when it’s true, it’s taboo. I feel it while writing this. That deep unease of saying something obvious that no one wants to hear: that certain environments really do grow minds differently. That time, intimacy, and attention can’t scale. That genius might be dying not because we lost the capacity — but because we lost the culture that made it possible.

We’ve built a system so obsessed with fairness that it would rather keep everyone average than allow anyone to stand too far above. Even if we could make this kind of education affordable for many, would society accept it? Or would we regulate it into oblivion in the name of equity?

This Isn’t Nostalgia — It’s An Autopsy

Not all progress feels like progress. Some things we’ve made cheaper. Faster. More accessible. And in doing so, we’ve hollowed them out. We’ve convinced ourselves that systems improve simply because they scale. That what’s new must be better. A hand-stitched rug replaced by IKEA fuzz. A Stradivarius swapped for plastic strings on a factory e-violin. But it’s dilution: mass production flattens the peaks.

Education followed the same arc. We traded slow craftsmanship for scale. Replaced intimacy with standardization. And in doing so, we made knowledge more available than ever, but often less transformative — brilliance doesn’t survive in bulk. The average kid today can Google the answer to any math problem. But how many of them have a real adult sit beside them and teach them how to think through the problem?

Yes, the industrial model of education lifted billions and leveled access. It gave us literacy, public schools, scaled knowledge. That mattered. Still does. But somewhere along the way, we stopped asking what we lost in the process. We stopped noticing the absence of the truly strange, the deeply original, the beautifully disobedient minds that used to shape the world.

Because they don’t just show up on their own. They’re cultivated. Slowly. Intimately. Not in classrooms of forty, but in moments of one-on-one.

The old world was rigged. Aristocratic tutoring was a privilege wrapped in silk and sealed with gold. But it created something we can’t seem to replicate: the groundbreakers. Minds that were not just smart but sublime. Not just well-informed but world-altering.

Today, we run the whole intellectual machine on competence quantity. We churn out well-polished résumés, uniform excellence, and “gifted” programs that filter for test-takers, not trailblazers. Our institutions are full of high-functioning mediocrity, not because people are less capable, but because the process that once shaped outliers has collapsed into a shallow, standardized grind. And we wonder why the spark is missing.

This is not nostalgia. It’s an autopsy.

Because the price of losing those minds is far more than intellectual — it’s existential. We live in a world on fire. A climate in collapse. An economic system cracking under the weight of its own greed. We need paradigm-shifters. Problem-solvers. Disruptors. And instead we’re building obedient technicians with perfect GPAs and no time to wonder why the world is falling apart, while the rest of us are eavesdropping on strangers' phones in the bus.

We didn’t just stop making Einsteins. We built a system designed to make sure they never show up in the first place.

So be loud.

The system is built in such a way that's making it difficult to even want to be a genius.

Take the technology sector, for example: innovation isn't rewarded as much as a good marketing. And any innovation hides behind a paywall. So you're forced to build something that can sell, not something that is necessarily useful. And people always make the cheaper and more comfortable choice - leaving better choices (for us, for the environment) mostly ignored. In this sector, the open source community is always the outlier - even though what they are building is built for everyone. Because convenience is what people are looking for.

Most artists are creating art/music that sells, not inspires. Same with films. Series. Books.

Scientists can only dive so deep into academia before they realise that a corporation would pay them four times as much for their knowledge.