The End Of The Antarctic Illusion: The Great Un-Freezing

The sky is falling — and resilience is breaking

March 2022. East Antarctica, the coldest place on Earth, morphs into something surreal. Temperatures surge 39°C (70°F) above normal in just three days — turning a typical −54°C into a near-balmy −15°C. Scientists at Concordia Station, normally bundled in layers against the brutal Antarctic cold, strip down to shorts and t-shirts, stunned by the most extreme heat wave ever recorded on the planet.

Then, the unthinkable.

Warm rain falls where it shouldn’t, and within hours, the Conger Ice Shelf — a mass of ice sheet the size of Rome — disintegrates into the ocean. No thunderous collapse, no Hollywood-style warnings — just a quiet vanishing act, like a city wiped from the map overnight. And clear warning: ice sheets are no longer passive observers of climate change. The kind of event that once took centuries now happens in days.

July 30, 2024. It happens again.

Another heatwave smashes into East Antarctica — but this time, in the dead of winter. Ground temperatures soar 28°C (over 50°F) above normal. The South Pole station logs its warmest July since 2002, averaging 6.2°C (11°F) above normal. From July 20 to 30, its temperatures resemble those of late February — summer conditions of a frozen world gone wrong.

And finally, The Great Un-Freezing.

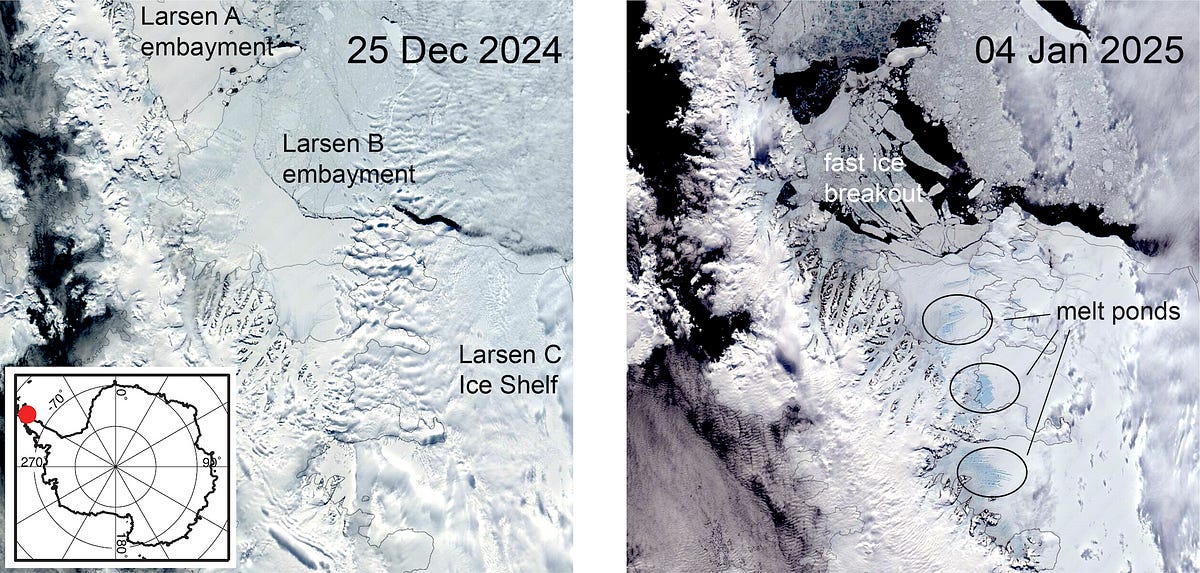

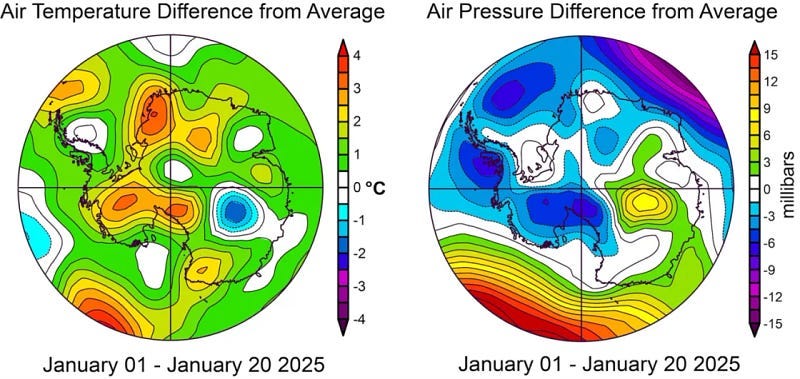

Throughout 2024, the Antarctic Ice Sheet experienced consistently above-average temperatures. After back-to-back hottest years on record, it came as little surprise when an unprecedented 3.7% of the Ice Sheet — an area the size of Texas — melted on January 4, 2025, only a week after the previous record set in late December 2024. The punch was particularly severe across the Antarctic Peninsula, where nearly half the region thawed, and by January 18, 2025, a second wave almost pushed another record.

But what’s really driving this meltdown? Surface temperatures certainly played their part. But the real force at work is something insidious, relentless, sweeping across the continent.

It’s the “rivers in the sky.”

Melting Winds

Atmospheric rivers have always shaped the planet’s weather, moving moisture across continents like invisible floodgates in the sky. But over Antarctica, they’re becoming something else: weapons of melt. And it all starts high above, in the stratosphere.

Like the Arctic, Antarctica has a polar vortex, a swirling fortress of high-altitude winds that locks in the cold. In theory, this vortex should be an impenetrable shield, keeping the frozen continent in a deep freeze. But in July 2024, atmospheric waves slammed into the vortex, weakening its grip and triggering a rare sudden stratospheric warming event. The result? High-altitude temperatures soared in a phenomenon that should only happen once every two decades and the polar vortex disruption persisted through early August, ultimately affecting sea-ice maximum extent growth in September.

The effects rippled downward.

Data shows that this sudden stratospheric warming event also impacted the lower atmosphere where weather occurs. As the stratosphere heated up, the jet stream — Antarctica’s protective wind barrier — weakened. And like a refrigerator door flung open, cold air spilled northward, bringing deep chills to New Zealand, southern Africa, and Patagonia.

The real problem was what came next.

With the freezer door ajar, that cold air left, and it also left a void. And nature doesn’t tolerate voids. Warm, moisture-laden air from the upper atmosphere surged south, drawn from the mid-latitudes into East Antarctica’s exposed interior. A clear path for the atmospheric “rivers in the sky” — long, narrow plumes of air that transport heat and moisture, typically associated with bringing extreme rainfall to the mid-latitudes and delivering meters of snow in the frigid Antarctic continent.

This time, instead, they delivered something far more ominous.

A new study by Gilbert et al. confirms the unthinkable: these rivers in the sky aren’t just bringing heat to Antarctica — they’re bringing rain. Liquid water onto a continent that depends on staying frozen.

And that changes everything.

Rivers In The Sky

West Antarctica already depends on atmospheric rivers to deliver a significant portion of its snowfall. In fact, research shows that despite only appearing a few days each year, these systems deliver about 13% of the continent’s total snowfall. But the problem, of course, isn’t the snow. It’s what happens when these same systems arrive with too much heat.

Some of the most fragile ice on the planet sits in the Amundsen Sea embayment, where ice shelves hold back the Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers. These glaciers already have a history of instability, with previous research warning that if their ice shelves collapse, it could set off a chain reaction, destabilizing the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet and eventually raising global sea levels by over three meters.

So, researchers analyzed two extreme weather events in the Amundsen Sea region in 2020 — one in February, mid-summer, and another in June, deep winter. They used three regional climate models to track how these atmospheric rivers interacted with the Thwaites and Pine Island ice shelves. The findings were stark.

Even in the dead of winter, when Antarctica should be locked in ice, and the atmospheric rivers dumped tens of meters of snow, it rained.

In the summer event, up to 30mm of rain fell on parts of the Thwaites ice shelf. In winter, when temperatures should be far too cold for liquid precipitation, 9mm of rain still managed to seep into the ice.

That may not sound like much, but in Antarctica, rain is an accelerant. It darkens the snow, making it absorb more heat. It seeps into crevasses, refreezing and forcing them wider apart, cracking the ice from within. And worst of all, it weakens the floating ice shelves that hold back the glaciers, making their eventual collapse not just likely — but inevitable. And in this part of the world, collapse isn’t just local — it’s global sea level rise.

The scale of what’s at stake is almost incomprehensible — if all of Antarctica’s ice were to melt, it would drive sea levels up by nearly 60 meters (195 feet), drowning cities, swallowing entire nations, erasing coastlines — and Antarctica’s contribution to sea level rise has already tripled in just a decade.

Suddenly, what seemed like a distant crisis isn’t confined to distant shores.

Subzero Rains

Antarctica’s cold climate and steep, angular topography make it unique. It also makes the region prone to rain in sub-zero temperatures.

First, there’s the foehn effect — when air moves over mountain ranges, warming rapidly as it descends. In Antarctica, this process is an aggressive ice-melter, particularly along the Antarctic Peninsula, the northernmost point of the continent. And over the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, where atmospheric rivers already bring heat and moisture, the foehn effect is intensifying. As air is forced over the mountainous terrain, temperatures spike, often pushing the ice shelves below past 0°C — triggering not just melting, but rainfall.

And here’s where things get even more unique in Antarctica.

Unlike most places on Earth, the white continent’s atmosphere is too clean for ice. In most clouds, tiny particles of dust and dirt act as “ice nuclei,” allowing ice crystals to form and snow to fall. But in Antarctica, these particles are almost nonexistent. That means clouds can remain filled with liquid water even when temperatures are well below freezing.

The result? When the foehn effect is strongest, there is often little or no rainfall because it evaporates before it gets a chance to reach the surface. But if rain is indeed reaching the surface, it’s easy to assume that it must be melting snow that passes through a warm layer of air. Research shows something else entirely: rain is most likely when the temperatures near the ground are close to freezing but not quite there — and even in regions where temperatures dropped as low as -11°C.

Supercooled drizzle — rain in subzero temperatures.

And that’s a problem.

The Illusion of Infinite Resilience Is Gone

I’ve always been drawn to Antarctica. Not just by the call of adventure, the echoes of Shackleton’s expedition, or the sheer vastness — but by something deeper. Infinity. The endless white, the unbroken horizon, the illusion of permanence — and the idea that some things, at least, were beyond human reach, untouchable and immune to time.

But now, I see what I never thought possible: an end to infinity.

Rain is falling in Antarctica. Heatwaves are tearing through the ice. Dormant volcanoes are peeping on the surface. And the Antarctic sea ice, once an impenetrable shield, has hit record low after record low, exposing the continent to even more warming. What once seemed unthinkable — Antarctica’s climate unraveling in real time — is now routine despite social media posts sharing a graphic comparing sea ice levels in the Antarctic on the same date 45 years apart, misrepresenting the data to suggest climate change is a hoax.

Rain is falling in Antarctica. Heatwaves are tearing through the ice. Dormant volcanoes are stirring beneath the surface. And the Antarctic sea ice, once an impenetrable shield, has hit record low after record low, leaving the continent vulnerable to further warming. What once seemed unthinkable — Antarctica’s climate unraveling in real time — has become routine, even as social media posts attempt to deny reality by misusing sea ice data from 45 years ago to dismiss climate change as a hoax.

Because the observational can’t be manipulated.

And what we are seeing — the melting, the greening, the diving — isn’t just another chapter in climate change. This is a shift from the predictable to a non-linear transformation that models struggle to capture but that we can already see with our own eyes.

And, as the saying should now be rephrased, what happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica. The Southern Ocean — our planet’s largest carbon sink — absorbs excess heat, slowing global warming at a cost we’re only beginning to understand. The Antarctic ice sheet, a frozen dam holding back tens of meters of potential sea level rise, is now cracking under the weight of our emissions.

2023 was the year climate change arrived in Antarctica.

2024 followed suit, confirming the fragility of the Earth’s frozen fortress.

And 2025 started with an unfreezing bang.

The paradox is almost unbearable. Antarctica’s collapse is terrifying — yet part of me feels relieved that the world can no longer look away: the South Pole enigma — the illusion of infinite resilience — is gone.

So be loud.

Thank you for your work. It's so difficult to imagine what this will really mean for us, isn't it?

The politics have turned away from accepting a massive mismanagement of our home - earth - and now has turned to a different orientation of managing the way far to many human by acquiring wealth and power concentrated in a few who can maintain their superiority by force . They are fools planning for a future that can not possibly benefit any life , even their progeny .

The idea of survival of the fittest might play out on a very large stage in the next hundred years on a much more hostile planet .