The Record-After-Record Trifecta: More Warming, More Heat Stress, More Carbon Dioxide

We just hit 430 ppm. 2°C could hit in five years. And extreme heat days are becoming the new baseline.

It started like one of those hikes that make you feel lucky to live in British Columbia — and forget the planet is on fire. Mild late spring, just before the mosquitoes and tourists take over the alpine. A steep push, sure — short trail, brutal elevation — but the reward was worth it: a glacial lake cradled by snow-speckled peaks, still holding onto the last breath of winter, its iced surface broken by melting intrusions threading down rock. The quiet pulse of a world that, at first glance, still looked like it had time.

On the way down, the air felt gentle at first — that post-hike relief, a breeze brushing against sweat.

But then something shifted, and the thermostat clicked into another gear. The kind of sudden heat that doesn’t build — it snaps, like a sauna door flung open in your face. The breeze turned into stillness; the warmth, into weight.

At first, I thought it was just me. You know how hikes go — you slip into these pockets of silence, just you and your thoughts pacing each other during those long inner monologues, even if you’re walking alongside someone. Maybe I was spiraling. A bit dehydrated. Imagining things.

Then we heard it: a bird—singing wildly, wrongly, like it had forgotten its own tune. I broke the silence.

“Did you hear that? It sounds like an adolescent bird learning to sing.”

She turned around and nodded, her face flushed red. And that’s when I knew the sauna theory wasn’t in my head.

The Inuit Raven, ancestor of song, teacher of respect — his first wisdom is this: if the birds stop singing what they know, something has broken. The bird was crying for help. It was suffocating from a sudden heat wave. That little frantic body was gasping in the same heavy air we were.

My girlfriend is one of the fittest and mentally strongest people I know. Glacier lake dips? She dives in. I stop at ankle-deep, pretending I’m “taking in the view.” But heat? Heat clips her wings. And this wasn’t just hot. It was wrong. Wrong in a way the forest felt too quiet, the glacier runoff too fast, the songbirds off-key. This was the kind of heatwave that doesn’t give your body time to catch up. And I realized, watching her wipe sweat from her temples, that we weren’t just overheated hikers.

We were witnesses.

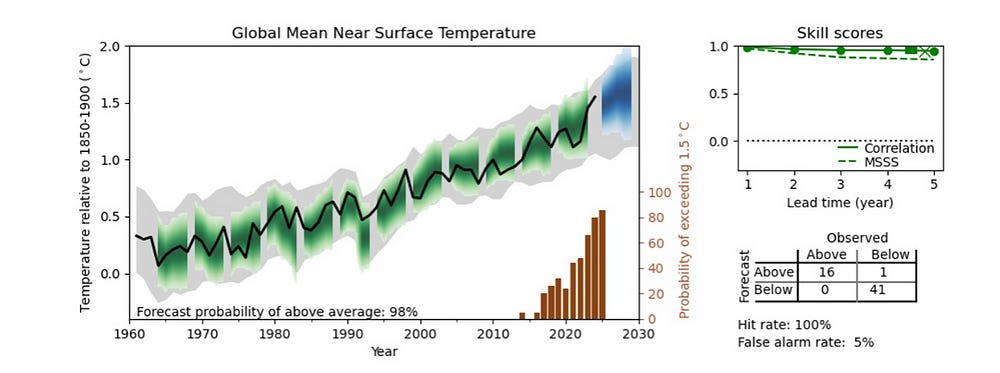

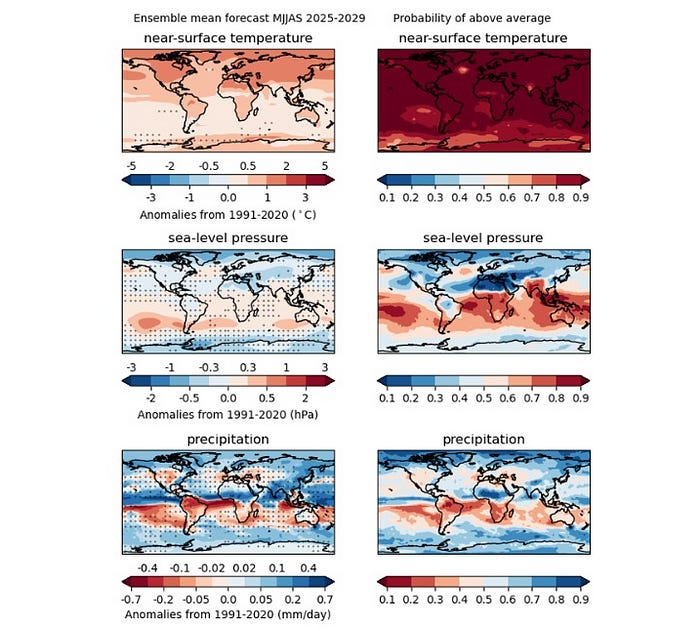

According to the WMO’s latest five-year climate forecast, global average surface temperatures between 2025 and 2029 are predicted to be between 1.2°C and 1.9°C higher than pre-industrial levels. There is now a 70% chance that the five-year average warming will exceed 1.5°C — a number we once spoke of as if it were a distant guardrail, a future to avoid. Now it’s just a statistical likelihood.

That number — 1.5°C, the so-called “safe” threshold — has been repeated so often it’s turned into climate wallpaper. Politicians chant it like a PR slogan. It floats on the surface of reports, summits, and corporate pledges. But what does it actually mean?

It doesn’t mean your morning coffee is 1.5°C hotter. It means your coffee plants might not exist. It means heatwaves that melt glaciers mid-hike and leave songbirds gasping for breath. It’s the difference between adaptation and collapse. Between food security and crop failure. Between livable summers and exile.

Unfortunately, we’re already there.

In 2024 — the hottest year on record, and likely the hottest in 125,000 years — we experienced our first full breach of the 1.5°C threshold. Now, what was once exceptional is poised to become “commonplace”.

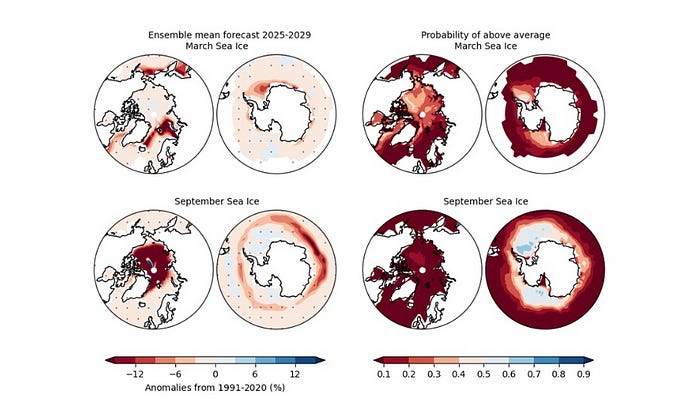

The WMO report suggests that this isn’t a blip. This is a floor, not a ceiling. The odds that at least one year between 2025 and 2029 will surpass 1.5°C have risen from 47% last year to 70% now. That warming isn’t evenly spread — the Arctic is set to warm at over 3.5 times the global average, reshaping ecosystems, jet streams, and global food patterns in its wake.

And no, a single year above 1.5°C doesn’t technically break the Paris Agreement. That’s measured over 20-year averages. This latest decadal climate forecast predicts that the central estimate of the 20-year average warming for 2015–2034 will be 1.44°C (with a 90% confidence range of 1.22–1.54°C). But let’s be honest: this is like arguing over definitions while your house is already on fire. Three single years above 1.5°C could kill the target. Twelve consecutive months? That could signal that long-term warming of 1.5°C is already here — and here to stay.

There’s even a small but newly emerged chance — 1%, according to the models — that we could hit 2°C within the next five years. That possibility didn’t even exist in the datasets a few years ago. The impossible is now plausible.

So no, the bird wasn’t singing out of tune. And no, that heat wasn’t just a “warm day on the trail.”

That was the sound of a planet crumbling to heat.

More Frequent Heat Is The Forecast

It wasn’t just us on that trail.

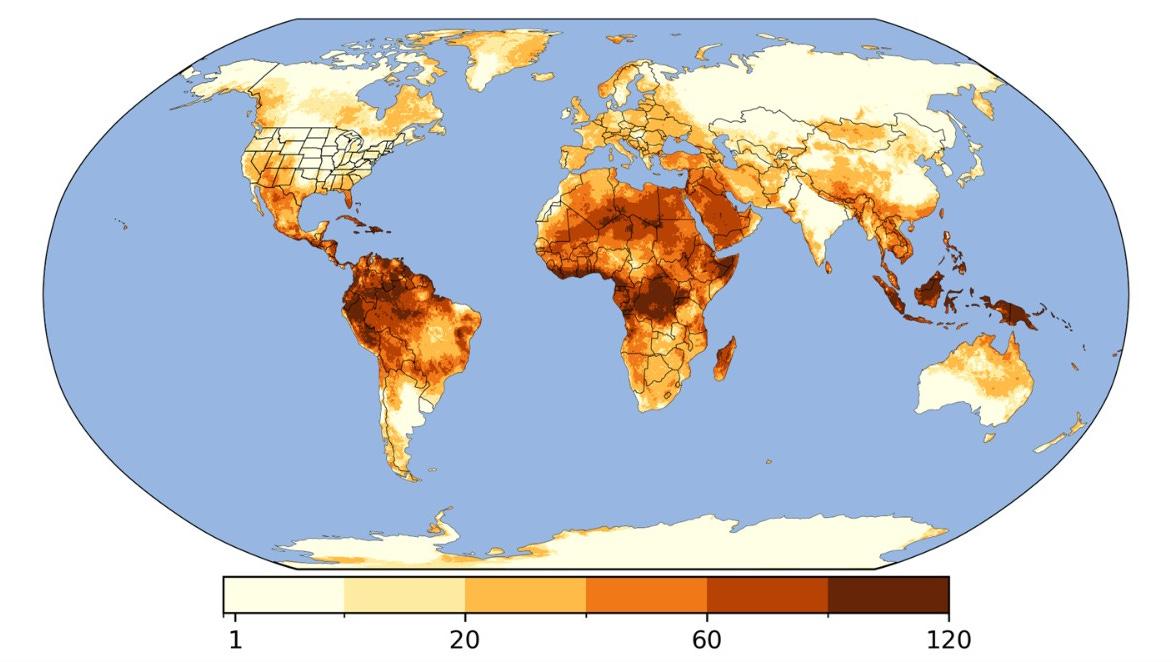

That same merciless heat had crept across continents. A lived reality for billions. According to a sweeping new global report, nearly 4 billion people — half of humanity — endured at least 30 days of extreme heat between May 2024 and May 2025.

Researchers calculated the number of days between 1 May 2024 and 1 May 2025 in which temperatures in a country or territory were above 90% of the historical temperatures from 1991 to 2020. The report chose the 90% threshold because heat-related illness and mortality begin to increase at those temperatures. Then, they used the Climate Shift Index to compare real-world temperatures to a modelled world without human-caused climate change, and what they found wasn’t subtle. It was global. It was everywhere.

Every country. Every territory. All of them now experience more extreme heat days because of climate change.

Take Aruba. It had 187 days — more than half the year — of blistering heat in the last 12 months. In a world without climate change? That number drops to 45. In the Federated States of Micronesia, 57 days were added to the heat tally. Islands surrounded by water, drowning in heat.

Every single one of the 67 major heatwaves over the past year — across the Americas, the Mediterranean, Africa, and Asia — broke temperature records, caused major harm to people or property, or did both.

That’s an unrelenting, body-breaking shift in the baseline of daily life. And that didn’t come from “just weather.”

This is what heat looks like now — from the killer waves in Mexico and Central America that claimed more than a hundred lives, to the deadly Mediterranean scorcher that turned tourist towns into infernos, to the 10°C-higher-than-normal March meltdown that gripped Central Asia in a fever it had never seen before.

Heat is no longer a season. It’s an assault.

And yet, it still flies under the radar. Floods and hurricanes may dominate the headlines, but heat is the deadliest extreme event we face. It kills quietly, through dehydration, organ failure, and strokes that don’t make the evening news. It’s invisible until the body gives out, until crops fail, until the grid collapses against the impossible feat of keeping the temperature down.

There’s a new baseline of what it means to be alive on a planet we’ve turned hostile.

Every heatwave now is more intense, more frequent, and more punishing because of human-induced, fossil-fuelled climate change. And no amount of air conditioning can save a species from cooking its biosphere.

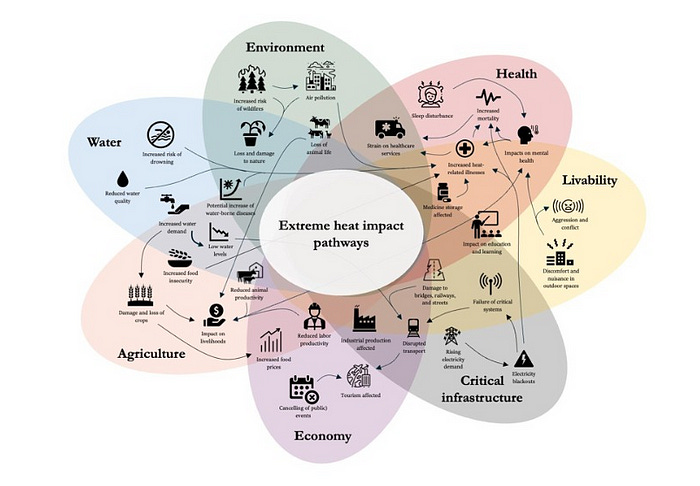

Disproportionate and Cascading Impacts

Extreme heat doesn’t just turn landscapes into ovens. It turns inequalities into death sentences.

Older adults, pregnant bodies, outdoor laborers, low-income families — they aren’t just “vulnerable populations” on a chart. They are the people gasping for breath in sweltering apartments. The ones collapsing in fields, warehouses, and delivery vans. The ones who already live closer to the edge, now being shoved off it by heat that doesn’t care what your job is, only whether your body can keep up.

And many bodies can’t.

Heat intensifies existing health risks, especially among the elderly and those with chronic conditions, leading to spikes in cardiovascular collapse and respiratory failure. Marginalized and low-income communities face this with fewer protections, less access to cooling, fewer clinics, and poorer housing. Meanwhile, outdoor and indoor workers without cooling clock in under direct assault from heat stress, dehydration, lost productivity, and sheer physical burnout.

And climate-driven heat has doubled the number of days considered dangerous for pregnant women in nearly 90% of countries and territories. For 63% of cities, it’s even worse. Maternal and fetal stress doesn’t announce itself with breaking news alerts. It accumulates silently, one overheated commute or sleepless night at a time. The toll is real.

These aren’t isolated symptoms. They’re dominoes. Push one down, the rest fall.

Heat saps agriculture. It shrinks water supplies, breaks down energy systems, floods emergency rooms, and erodes the lifelines of the working poor. And often, it doesn’t come alone. It teams up with droughts, with power outages, with food shortages, and even with violence.

Our bodies are tuned like violins to a specific range. The average human temperature is 37°C. Push that by a degree or two, and we’re in fever. Push the air we breathe beyond 22°C, and our brains work more slowly. Our attention fractures, our judgment slips. The heat isn’t just uncomfortable — it’s disorienting.

That’s why we sweat. That’s why we chase cold rooms and shaded streets. But even that has its limits.

When the air’s too hot and the humidity is too high, our cooling systems break down. Wet-bulb temperatures — the threshold where sweat stops helping — are already being crossed. At 35°C wet-bulb, your body can’t cool itself. Not in the shade. Not with water. Not even if you stop moving.

Beyond that, survival isn’t guaranteed.

Millions are living in the slow burn toward the next threshold.

Because the climate system isn’t the only thing overheating. So is the social one. And neither has a built-in emergency brake.

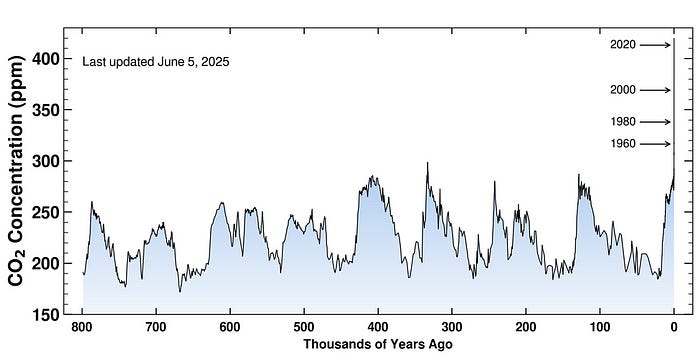

We Just Hit 430 ppm — Nothing About That Is Normal

Earth’s atmosphere now has more carbon dioxide in it than it has in at least 800,00 years. The last time the planet had such high levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere was likely more than 30 million years ago, long before humans roamed Earth and during a time when the climate was vastly different.

For the first time, the seasonal peak of carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere exceeded 430 parts per million (ppm) at NOAA’s Mauna Loa Observatory on Hawaii. The May monthly average of 430.2 ppm for 2025 was an increase of 3.5 ppm over May 2024’s measurement of 426.7 ppm.

And it’s not just the number. It’s the pace. In 2013, scientists gasped when we crossed 400 ppm. Now, the May monthly average of 430.2 ppm for 2025 was an increase of 3.5 ppm over May 2024’s measurement of 426.7 ppm. A 3.5 ppm jump in just one year, something that used to take 2,000 years.

We built our entire society during the soft lull of a cooler world. We planted crops, settled coastlines, planned cities, built economies — all around a stable climate that no longer exists.

For the last 400,000 years, carbon dioxide followed a natural rhythm: a 100 ppm rise meant about 5°C of warming, stretched over millennia, driven by Milankovitch cycles — gentle tilts in Earth’s orbit. That rhythm is over. We’ve poured rocket fuel on the beat.

In just two centuries — a geological blink — we’ve cranked CO₂ from 280 ppm to over 430 ppm. The last time CO₂ rose this much, it ended the last Ice Age. That took 10,000 years. We did it in less than 200. A lightning bolt in geological time.

This doesn’t mean we’re automatically locked into 5°C of warming. The climate isn’t a thermostat. It’s a giant ship — slow to steer, but catastrophic once it turns. What we’re living now is the delayed echo of a 370 ppm world. Thanks to the lag effect, the full violence of 430 — or 500 — hasn’t even arrived yet.

But nature can’t sprint to catch up. Trees can’t run uphill. Coral can’t pack a bag. Most species, including us, evolved within narrow climate bands. When you push them out, they don’t “adapt.” They disappear.

Every year, we burn 400 years’ worth of buried sunlight — coal, oil, gas forged from ancient forests and plankton — just to keep the lights on and the wheels turning. We’re melting prehistoric time into megatons of heat. Into storms. Into tipping points.

And we are not slowing down. Even the best-case scenarios — the pledges, the promises, the “net zero” smoke shows — land us deep into overshoot. As well as 2° C of warming, 550 ppm is within sight. That’s two ice ages in reverse. The Great Dying — the worst mass extinction event in Earth’s history — but compressed into the timespan of a few human lives.

A handful of nations, names, and corporations — the planet-wreckers fattened by centuries of combustion — keep the system running by predatory design. They stall. They greenwash. They profit from the fire. And we call it business as usual.

We’ve become the human asteroid. But this time, the extinction isn’t caused by cosmic chance. It’s engineered with cement mixers and Excel sheets. With offshore accounts and air conditioning.

It shows up not with a bang, but with a flicker. A crack in the grocery budget. A food swap. A power bill that makes you hesitate. A lukewarm shower. A canceled vacation. A toddler waking at 3 a.m. because the night won’t cool down.

No sirens. No bulletins. Just life shrinking. Quietly.

And no electric car, no eco-label, no metal straw will reverse what’s already locked in. The damage is cumulative. The crash has already happened — we’re just living through it in slow motion.

This system — the one that made fossil fuels the currency of power — doesn’t have a reverse gear.

How poetic.

How cruel.

The Frantic Note Is Inside Us

That sharp snap of heat on the trail — the one that silenced the breeze and twisted the bird’s song into a cry — didn’t just happen in the forest. It’s the new rhythm of the world we live in now; the frantic note is inside us.

If this crisis feels overwhelming, it’s because it is. You’re grieving a future that was promised and stolen. You’re mourning stability. But grief is not weakness — it’s proof that you’re awake.

Feel it. Let it burn under your skin. The system wants you numb, scrolling through endless distractions, quietly surrendering, watching the world tilt, and pretending it’s normal. It drowns out the questions that cut to the bone, starting with: What if survival demands dismantling the very hunger for “more”?

Numbness is the slow death of resistance. Polite optimism is the cage we’ve built around ourselves to stay sane. And hope is no longer a comfort; it’s a confrontation.

Hope is standing on the edge of collapse, shouting the truth, and still choosing to fight. Earth will outlast this collapse. Our fight is to preserve the flicker of humanity amid the chaos: humility that admits failure, solidarity that demands justice, and love forged in dirt-stained hands planting seeds of resistance.

This decade will tear us apart — but it will also make or break us.

Scream until your voice cracks. Plant seeds in the scorched earth. Write the stories no one wants to hear. Stand in the way of the bulldozers. Hold your neighbor when the world breaks. Mourn what’s lost. Defend what remains. Imagine what’s still possible.

The heat snapped open the door. Now, it’s up to us to decide if we step through.

So be loud.

All your articles are incredible. It's good to know that I'm not alone with my fears and that you nevertheless manage to find some kind of hope. Thank you

"We’re melting prehistoric time into megatons of heat. Into storms. Into tipping points."

Beautifully written.